The first five times the sales manager of Keneya Jemu Kan came looking for Madame Togo Kadiatou Mallé to talk about her women’s association selling condoms and other health products, she ran away and hid, so terrified was she of the prospect of having to work with condoms.

But the sales manager’s persistence paid off. Eventually, they talked, and Madame Togo has become such an enthusiastic condom promoter, she is known as “Mama Condom.” She laughs about the fear she once had of condoms.

Madame Togo is president of Muso Yiriwa Ton (MYT), which means “women-empowering group” in the Bambara language. It is a women’s association based in the very poor Sabalibougou neighborhood of Bamako, Mali. Her association – as well as other women’s associations – are a major reason for the success of Keneya Jemu Kan (“Communication Around Health”), or KJK, a project funded by the U.S. Agency for International Development and led by the Johns Hopkins Center for Communication Programs that seeks to reduce maternal, infant and child mortality in Mali. Palladium leads the social marketing component of KJK.

MYT has more than 400 members, and roughly half of them sell the KJK’s male and female condoms, as well as Aquatabs (water purification tablets), Orasel Zinc (zinc tablets and oral rehydration solution to treat diarrhea), and CycleBeads (a natural family planning method). MYT members sell an average of 107 cartons of Protector Plus condoms per month. That’s 64,200 condoms. The partnership helps to enhance economic prospects of its members.

“It has become a source of life for many families,” said Madame Togo. “And it is improving health of the areas where they sell.” in Commune 5 and beyond.”

Overcoming Obstacles

MYT works with local authorities – including imams, priests and pastors. Many of these religious leaders used to be against condoms, but MYT was able to convince most of them to accept condoms as a health product. MYT members don’t sell inside mosques or churches, but have no problem doing so outside. The older men will ask for a Cube Maggi, a popular ingredient for making food tasty. That’s a secret word for condom, a word most of them would be nervous about saying aloud.

One of MYT’s best condom sellers is Kadiatou Samake, age 19. She used to work in MYT’s hair salon. Then she found she could make more money selling condoms. Now she sells five to six cartons per week (there are 600 condoms in each carton), and she earns 2,500 CFA francs on each carton. That’s about $4.25 in U.S. dollars.

Her winning strategy is to visit “hot points,” places where there is a lot of sexual activity, like hotels and night clubs. She asks to see the manager, makes the case for her product, and builds relationships with clients and potential clients.

Aminita Djiré, 17, is another top condom seller of MYT and mother of a 15-month-old baby. Her selling prowess is such that her nickname is Condoms Diatigi (“representative of the condom”). She also sells five to six cartons of Protector Plus condoms per week. Like Kadiatou, she goes to the hot points and nurtures her contacts. “Even if they don’t buy,” she said, “I give them information and take their contact information.”

Improving Community Health

Madame Togo claims that MYT, with the support of KJK, has made a significant impact on behavior change in the communities where they sell products. For example, she says that Aquatabs has become an indispensable product to ensuring clean drinking water.

Although MYT’s biggest sellers are male condoms and Aquatabs, the first quarterly report of the project’s last year cited the fact that Protectiv female condom and CycleBeads sales exceeded objectives. The community-based distribution of MYT was identified as one of the reasons for these sales.

Professor Mamadou Traoré, a gynecologist and obstetrician, is the chief doctor of Commune 5, where MYT is based. Commune 5 is one of the poorest of the seven communes of Bamako. In terms of amenities, it is more like a village than an urban area. For example, there is no piped water in Commune 5. He says there is also a lot of promiscuity.

Traoré reports that the contraceptive prevalence rate in Commune 5 increased from 10.5 percent in 2015 to 14.2 percent in 2018. That’s an increase of almost 4 percent in three years. There are surely many reasons for that, but he believes that the work of Muso Yiriwa Ton is one of them.

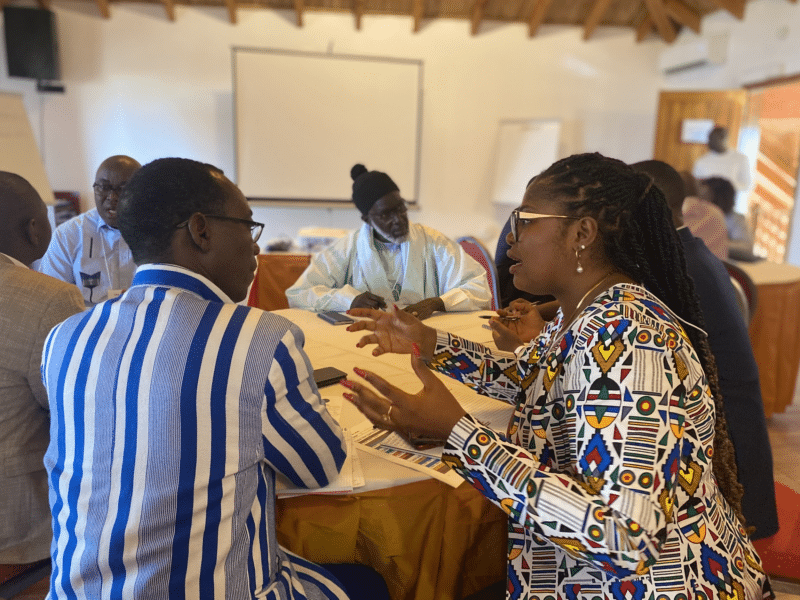

Women’s Groups Are Having an Impact

KJK is also working successfully with five other women’s groups in Bamako and the regions of Kayes, Mopti and Sikasso and finding that women’s groups, particularly those in rural areas, can help “reach the last mile,” meaning those people living in remote or neglected areas that are not served well by public health clinics or private sector retail outlets.

KJK knows this approach works in different areas of Mali and believes it can also work in different countries of Africa. KJK is building capacity in these women’s organizations so that they can continue supplying products when the current project ends WHEN. KJK hopes to eventually link the women with existing commercial distributors so they can continue their important work.

David J. Olson is a consultant with Palladium. A version of this post originally appeared on the website of CCP’s Knowledge for Health project.