When researchers from the Johns Hopkins Center for Communication Programs distributed a survey asking people in Senegal whether it was acceptable for a husband to hit his wife, most (81 percent of men and 92 percent of women) said “No.”

But when CCP conducted more in-depth research as part of the Neema program, a USAID-funded health initiative, the men and women they met told a different story.

“It’s normal to be beaten,” one woman told the researchers.

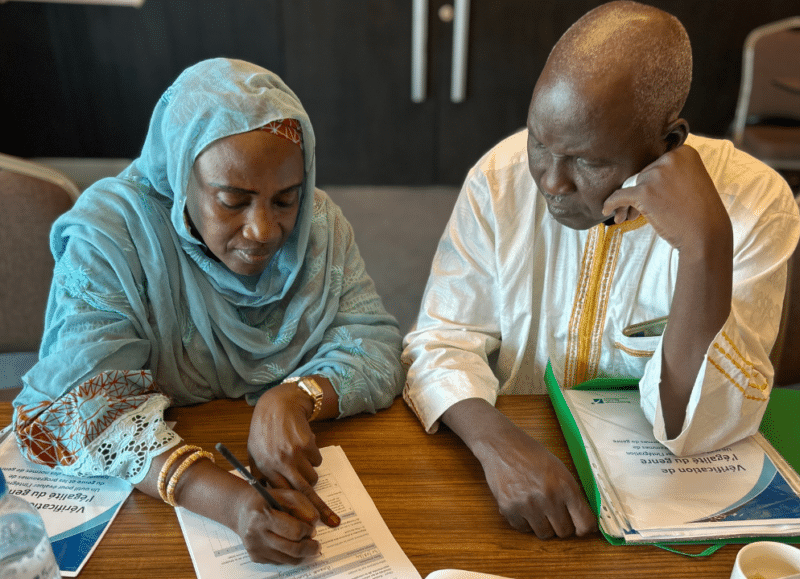

Twenty-eight focus groups that comprised a total of 297 men and women met in seven regions of Senegal to discuss how and why gender-based violence exists in their communities.

“Through this research we were hoping to understand how the various forms of violence, such as emotional, physical and sexual violence, might be connected, from both men and women’s perspectives,” says CCP’s Tim Werwie, MPH, MFA, who published an analysis of interview data in the Journal of Family Violence on April 19.

Physically and sexually violent behaviors have been associated with decreased use of family planning, reduced agency of women to make health-seeking decisions, their disproportionate exposure to HIV and other illnesses and more.

Reducing gender-based violence, researchers hope, could lead to more favorable gender attitudes and gender equality in households and, ultimately, improve general community health through increased access to and use of services by women.

Many of the research findings in Senegal were strikingly similar from men’s and women’s perspectives. Husbands and wives both engaged in emotional violence, frequently rooted in household financial struggles, including the enforced financial dependence of women on their husbands and the deliberate withholding of resources by men, or humiliation and verbal ridicule by women at their husband’s inability to provide for his family. The emotional violence between spouses then often escalates to physical violence.

It is only women, however, who suffer from physical violence.

Both men and women described what they considered an “acceptable level” of day-to-day physical violence – for example, slapping or hitting that doesn’t cause physical injury or visible harm – as a normal and appropriate way to discipline a “misbehaving” wife. “I hit her. It’s normal. I have the right,” one man from an urban area told a focus group. “I’m the man and when I decide she oversteps [her bounds], I correct her.”

Most men and women agreed, however, that physical violence became “unacceptable” once it caused visible harm or injury.

Said another man: “Beating [your] wife is normal. It is to put her back on the right path … but without hurting her.”

At the same time, the data showed that the perceived ability of women to bear the conditions that cause them to suffer is held in high regard, creating a social incentive to endure life’s hardships – including being beaten by their husbands – without complaint.

“Through this concept of endurance, we found a way that violence against women is normalized in many communities in Senegal,” Werwie says. “It is just considered an acceptable part of life that ‘strong women’ are able to endure.”

CCP is now working with local partners to reduce or eliminate gender-based violence through strategic messaging and programs in these regions of Senegal.

“One way forward is to use CCP’s expertise in health messaging to reframe all physical violence as unacceptable and to reimagine the local concept of a ‘strong woman’ to not include the endurance of suffering and physical violence,” Werwie says. Messages are being designed for radio, television and other community events.

The CCP team is also exploring ways to improve communication between spouses through a human-centered design process. By reframing the tolerance of violence and improving communication between couples, it may be possible to disrupt the pathways that escalate to physically and sexually violent behaviors, Werwie says.

“Gender-Based Violence in Senegal: its Catalysts and Connections from a Community Perspective” was written by Timothy R. Werwie, Zoe J-L Hildon, Abibou Diagne Camara, Oumoul Khairy Mbengue, Claudia Vondrasek, Mamadou Mbaye, Hannah Mills, Kuor Kumoji and Stella Babalola.