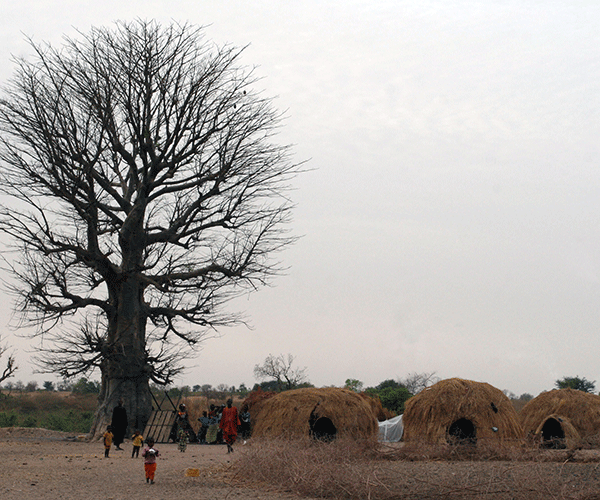

A stone’s throw from the edge of Paoskoto village in Senegal’s interior, a collection of branch and stick huts sit dotted about in a field of old peanut shrubs. This small gathering of the nomadic Fula tribe has settled here briefly to trade with local farmers and find pasture for their livestock. Milk and meat exchanged for grain and mobile phone credit.

Inside their domed huts, metal-frame beds and well-stowed kitchenware give the impression of settlement. But these are some of the hardest people to reach in universal health campaigns because they are often on the move. Haji Dia and his wife, Feincoura, have six children, ranging from toddler to teenager. Dia feels he has been successful in life.

“I have 150 cows now,” he says, proudly scratching the waddle of his favorite bull, who squints his eyes in pleasure.

Despite his bovine success, Dia admits that malaria has always been a serious problem for his family.

“Before [these nets came] we didn’t use any at all and the mosquitoes were really bothering us! Our children were constantly falling ill with malaria. This was very difficult for us.”

The Dia family and three other Fula families travel together. During the rainy season they stay in their birth village, Daara, hundreds of kilometers to the northwest on Senegal’s ‘Great Coast’. But when pastures run dry at home, they travel inland in search of water and food for their livestock.

“We nomads,” Dia says, “often live out in the open bush where there are many mosquitoes. We have nothing to protect us. The mosquitoes really attack us.”

According to Dia, ten members of their group have died from malaria in the past few years.

“Often we camp in remote areas, far from hospitals. So the time it takes to bring someone to a health center, they are almost too far gone by the time they arrive.”

Dia says he first heard about the net distribution campaign over the radio. Aside from his battered mobile phone, his radio is the only other sign of modernity in the camp.

NetWorks uses the vast network of community radios across the country, and will soon engage national broadcasters in the capital Dakar, to make sure they reach the most remote corners of Senegal with their message: “Mosquito nets must be used by all the family, all year long, every night, because the mosquitoes are always there.”

Radio is often the best, and sometimes the only, means of communicating with mobile communities like Dia’s.

Doctor Mamadou Doucouré of Nioro District health center has been very involved in the drive for universal coverage. He says communication is an essential part of the job.

“For me, good communication in a campaign like this is fundamental to the campaign’s success. [Good communication] means the population is well aware of the distribution days in their area but also how to use the net properly, how to wash it.”

Doucouré adds that the success of this universal coverage campaign is largely due to the strong partnership between Senegal’s Ministry of Health and NetWorks, especially at the local level.

Inside Haji Dia’s round hut, three metal-frame beds circle an open sandy space in the center. Each bed has a rectangular white net, its four corners tied to branches poking down from the ceiling, the bulk of the net wrapped neatly over itself.

It seems Dia got the message. He smiles and hugs his youngest daughter.

“With these nets,” he says, “we are much better protected. The mosquitoes cannot get through the nets and neither can the flies. Our children are protected and so are we.”

As the sun sets on the camp, a herd of long-horned cows trundle into the clearing from a day’s munching.

“As nomads, we are often on the move to find pastures for our cows,” says Dia. “We don’t carry many possessions. We can travel far into the bush where there are no houses or huts, where there is nothing and put our mattresses on the ground to sleep.”

“Now we hang the mosquito net from a tree and we are protected. For us these nets are very important.”

NetWorks is a five-year, USAID-funded global project that seeks to improve and establish sustainable net access and use. JHU∙CCP leads the project’s efforts on Senegal’s universal coverage campaign on long-lasting insecticide treated nets (LLINs).