In Swaziland, preventing HIV/AIDS depends largely on the talents of people like Bhekie Sithole who can lead opposing factions to common ground. As Program Officer for Key Populations (KP) for CCP’s Health Communication Capacity Collaborative (HC3) Swaziland, Bhekie brings together men who have sex with men (MSM) and sex workers with health workers and police for conversations designed to overcome stigma and promote HIV/AIDS prevention and treatment efforts.

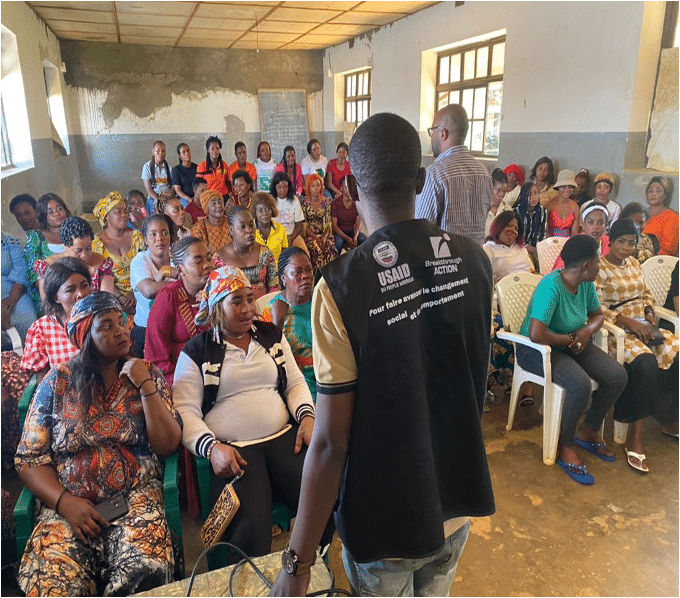

HC3 Swaziland seeks to eliminate socio-cultural and gender norms that create barriers to testing and care and increase the potential for infection. The project also aims to improve access to prevention of mother-to-child transmission (PMTCT) services by empowering communities to lead social and behavior change communication (SBCC) strategies and bolstering acceptance of services and healthier behaviors.

His family’s eldest son and caregiver for his siblings, Bhekie speculates that his own parents likely died of AIDS-related illness because they were too ashamed to seek treatment. Bhekie’s personal and professional experience has made him a perfect fit for HC3’s efforts to strengthen channels for social and behavior change communication (SBCC) in the campaign against HIV/AIDS.

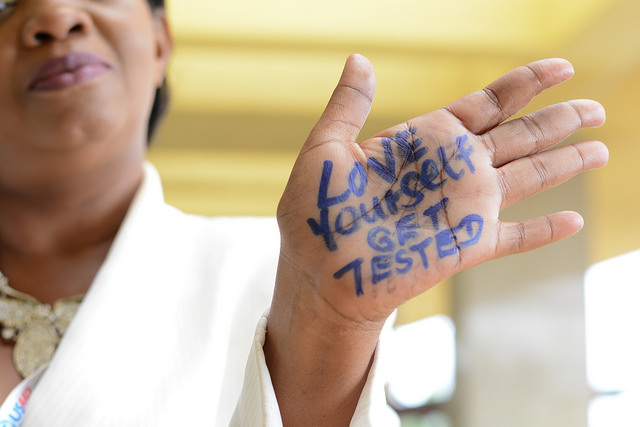

It wasn’t until his friend was near death that Bhekie Sithole discovered he was suffering from HIV/AIDS. Although antiretroviral therapies (ART) were available, “he was probably not taking them because of the stigma of being a man who had sex with men,” Bhekie says.

His friend’s painful death was a wake-up call. “I suspected that many others like him were in the same situation: HIV-positive and afraid to access health care services.” Bhekie began to mobilize his peers in an effort to share information about HIV, available treatment and the deadly consequences of stigma.

When the conversation began, “People were really, really relieved,” Bhekie says. “People started to talk about safe sex.”

His college activism set Bhekie on a course that continues today in a country with the highest prevalence of HIV in the world. He is committed to helping his nation overcome the sense of shame associated with sex that hampers MSM and sex workers from receiving HIV-related information and treatment.

A willingness to openly practice what he preaches about HIV/AIDS has made Bhekie the catalyst for communication among colleagues, peer organizations, the ministry of health and KP. His straightforward approach has gained the trust of KP who often live in social isolation with no access to life-saving information. “For instance, we know that knowledge about HIV-related issues is quite low among key populations and we started to conduct trainings based on that,” Bhekie says.

It’s also a persistent challenge to get assurance from health workers that they will give KP fair access to the trainings. “People are doing this work, but they still have personal feelings that thwart our goals,” Bhekie says. “We’ve worked hard to change their bigger thinking and perceptions.” Essential as well is making sure “that the key populations are involved in these discussions to alleviate their mistrust of the medical and law enforcement sectors.” It’s a balancing act, Bhekie says.

He continues to enhance his grassroots work with research. To complete his graduate degree, Bhekie wrote a thesis on HIV-related needs of MSM and received extensive training in the field. “So I come to these conversations with experiences, examples and the ability to lead sensitization activities.”

Although stigma remains a formidable problem, Bhekie, a frequent co-author on journal articles about health communication and HIV prevention, sees progress. “Key populations are becoming empowered to stand up and access services,” he says. As Bhekie and others reach out to KP, NGOs and community organizations, “All those voices are changing the status quo.”