The system seemed simple: Share the health benefits of birth spacing and modern contraceptives with Nigerians and help connect those who are interested with local health clinics providing IUDs, birth control pills and other family planning methods.

What the leaders of the Johns Hopkins Center for Communication Programs’ Nigeria Urban Reproductive Health Initiative (NURHI 2) didn’t anticipate was that health clinics would rebuff so many of the women they sent for contraception. In order to get providers to actually provide family planning services, CCP knew it had to change its approach.

“We thought just creating demand and training service providers would be enough, but it wasn’t,” says CCP’s Rael Odengo, the Baltimore-based program officer for NURHI. “We were telling people they could come for any service, that the contraceptive methods had very few side effects, but the providers were turning clients away.

“Unmarried people who want family planning, you’re turned away. Newly married couples, you’re turned away. You have only one baby, you’re turned away. This wasn’t how it was supposed to work.”

The NURHI team determined that it was the deeply ingrained cultural and religious beliefs of the service providers themselves that appeared to be standing in the way of a successful family planning program – even though the providers had been trained by NURHI to offer these services to all comers. These biases, feelings that certain women shouldn’t be eligible for contraception, were interfering with their work. For example, many Nigerians believe newly married couples should have children right away, or that people with small families should have bigger ones, or that women need the written consent of their husbands to receive contraception.

“They were not adhering to our protocols but were instead allowing their perceptions and beliefs to determine who was eligible for certain contraceptive methods and who was not,” says Saratu Olabode-Ojo, a senior technical advisor for NURHI 2.

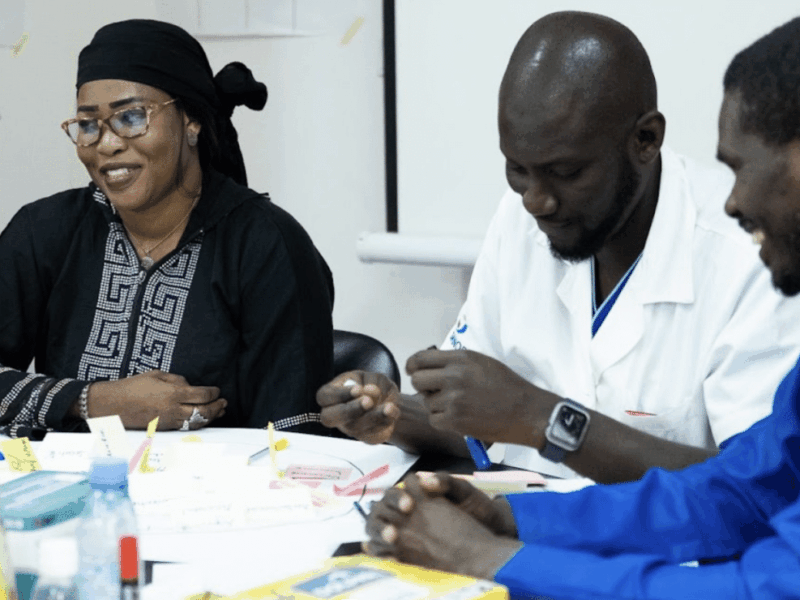

To get to the bottom of this issue, the NURHI team engaged in human-centered design workshops. By bringing in clients and providers to sessions where they just listened to one another to better understand what was standing in the way, the workshops gave the service providers the opportunity to identify their own problems and then develop solutions to this sticky issue. NURHI is a comprehensive Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation-funded program designed to eliminate supply and demand barriers to contraceptive use and make family planning a social norm in Nigeria.

“I will only provide condoms not other methods to young unmarried girls,” one provider said during a session. “Why? It can be given to prevent pregnancy and [sexually transmitted infections]. I will provide other methods to couples with one or more children. Why? Because if she could not conceive later, I will be blamed for giving her drugs that prevents her from conceiving.”

In the meantime, providers have received new intensive training that asks them to put themselves in the shoes of clients who want to prevent pregnancy and to help them understand that it is their job to help them obtain modern contraception regardless of their personal beliefs. Olabode-Ojo says this helps some providers understand that allowing all types of women who want contraception “is not wrong.” This has helped facilitate better dialogue between providers and their clients, she says.

Some of these providers are also leading community conversations with men and women to discuss many facets of family planning.

“The biggest challenge we had was communication,” Odengo says. She admits that there’s still a long way to go. Many women still fear having conversations about family planning with their own spouses while many providers still believe that spouses need to consent. “We are trying to change the mentality,” she says.

The approach seems to be working. In a nation where low use of family planning has long been a seemingly intractable problem, visits to NURHI clinics in Kaduna, Oyo and Lagos are up significantly between year one and year two of the program, with visits nearly doubling in Kaduna and nearly tripling in Oyo. While not all of it is due to addressing provider bias, Olabode-Ojo and her colleagues believe it is playing a significant role.

“Things are really, really starting to change,” she says.