The power of storytelling to make us laugh and make us cry – especially make us cry – was on full display yesterday morning as David Isay went through his presentation.

Isay, a longtime radio documentary producer, founded the oral history project StoryCorps, which allows people to record interviews with their loved ones and have the conversations archived in the Library of Congress. Half a million people have shared their stories with StoryCorps since it began in 2005, which has been described as “America’s empathy machine.” A tiny fraction of the tales have been edited and played on NPR stations around the country.

He was speaking at “Stories + Data = Change: The Evidence on Storytelling for Global Health,” an event sponsored by the USAID-funded Knowledge for Health (K4Health) project, led by Johns Hopkins Center for Communication Programs, and FP2020.

Isay played some snippets: A black adopted son of a white mother talking about the heartbreaking day when he was severely beaten by Denver police because of the color of his skin. The New York couple sharing their profound love as the husband lays dying. The brave 10-year-old recounting to his mother what happens during an “active shooter drill” in his Houston elementary school.

“The idea of StoryCorps is connection with another person,” he told those gathered. “We don’t care if you’re a good storyteller. We care if you have a meaningful experience in the booth.”

He called the whole experience transformative – both for the people who are sharing their stories and those who later get to listen – in that it allows people to just talk about their lives.

“I love the power of the human voice,” Isay said. “When you’re in the car, listening to a mother and son talking about active shooter drills, it’s like they’re whispering in your ear. It’s like an adrenaline shot to the heart.”

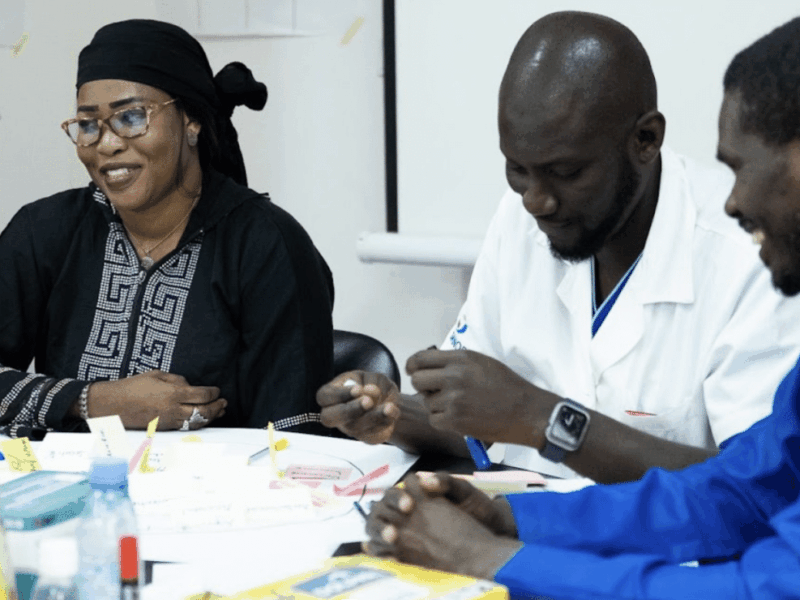

Tara Sullivan, MPH, PhD, director of the K4Health project and director of knowledge management at CCP, spoke of CCP’s journey to its storytelling initiative Family Planning Voices, which was launched in 2016 with FP2020. “The family planning community had begun placing a heavy emphasis on the need for data in decision-making,” she explained.

“While we recognized and agreed with the need to collect and analyze data, we noticed another equally important trend: that people working in family planning had important knowledge to share with each other, knowledge that went beyond the data, and they needed a platform to share their knowledge and experience,” Sullivan said.

Inspired in part by StoryCorps, the result was FP Voices, which has published stories from hundreds of people in dozens of countries. The result is unassuming portraits and a few heartfelt words, shedding light on the unscripted personal stories behind family planning data, while driving momentum and fostering community around the global family planning movement.

“Stories and data are often painted as opposite sides of the spectrum. The qualitative vs. the quantitative. The ‘soft’ side vs. the ‘hard’ numbers,” Sullivan continued. “What we’ve learned over the past two years, and what we hope to impart through today’s program, is that this way of thinking is outdated. Stories and data are each types of evidence with equal value and relevance. Stories give us data, and data can tell a story. The key is learning how to use each to its advantage and for maximum benefit for our programs and professional communities.”

The work of Paul Zak, PhD, director of the Center for Neuroeconomics Studies at Claremont Graduate University, aims to figure out why stories are so powerful – and how to use them to persuade people to take action. The sweet spot of stories that inspire are those that grab attention and make you care, he explained, and it has a biological component.

He spoke of experiments where he hooks people up to sensors that measure how and where in the brain people respond to different stories. He spoke of taking people’s blood before and after storytelling to measure levels of oxytocin in the body, a chemical that has been called the “love molecule” because it drives the urge for human connection.

He has measured brain activity in people who are watching Super Bowl ads and compared the results to what reporters at USA Today said were their favorite commercials during the game.

What they found, Zak said, was that “there is no correlation between what people say they like and what tickles their brains.”

He has used this knowledge to help advertisers create commercials that inspire people to take action and help the military create and test stories to facilitate conversations that can reduce conflict. He says that messages that create social connections make people more likely to take action. “You need to embrace your ability to persuade people,” he said.

CCP’s Sullivan said the event reinforced the notion that “stories can be a catalyst for change and bring us together as a community.”

“If there is one thing we hope you take away from today, it is that stories are a powerful way to share knowledge, and research shows they evoke empathy, create trust and lead to action,” she said.

A recording of the event can be found here.