The paint was peeling off the Isolo Road health clinic in Lagos, Nigeria, both inside and out. The counseling room where women came to discuss family planning, with its mismatched furniture, lacked privacy. The room where providers inserted IUDs and contraceptive implants had rusting old equipment and no curtains covered the windows.

And the worst part: Very few women in the poor community it served were actually using its services. In February of 2016, only 93 women received a modern family planning method at Isolo Road.

But just one year later – six months after a 72-hour clinic makeover led by the Johns Hopkins Center for Communication Programs’ Nigerian Urban Reproductive Health Initiative (NURHI) – visits were up exponentially, with 1,150 women a month receiving modern contraception there.

“The transformation has been incredible,” says CCP’s Rael Odengo, the Baltimore-based program officer for NURHI. “The environment is more appealing, the equipment is up-to-date, the service providers are better trained and – most importantly – women in the community are now getting the proper health care they need.”

Government-run health facilities throughout Nigeria are often in such poor condition – and the providers so inhospitable – that many Nigerians avoid them. Meanwhile, Nigeria has some of the worst maternal mortality rates in the world: A Nigerian woman dies every 13 minutes. And immunization coverage for preventable childhood diseases is only 33 percent.

There is a lack of trust between communities and clinics and many would-be patients seek out less conventional methods of treatment, leaving them without appropriate prenatal or pediatric care.

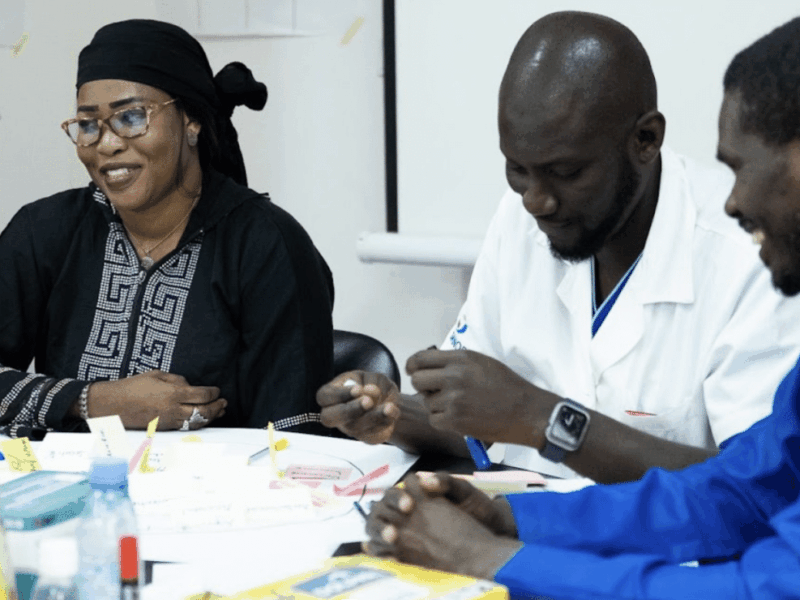

The 72-hour clinic makeover was designed to repair that trust, helping communities and providers work together to fix what’s wrong. The makeover itself may be quick, but months of planning and preparation goes into determining what needs fixing and how it will be accomplished. NURHI prioritizes facilities in high-population areas and involves the government, service providers and the local communities with every step of the process.

Together, they determine what a clinic needs and develop a plan to make the changes.

In one community, a broken water pipe kept clean water from the clinic for nearly a decade. They had been told the cost to make the repair was prohibitive. Working together with NURHI during a makeover, the repair was made at a fraction of the cost.

Another community may need medical equipment or new waiting rooms or privacy screens. Service providers receive additional training to improve service delivery. Local artisans are selected to repair tiles or doors or paint walls, whatever the community and providers determine is needed. None of the makeovers cost more than $800 U.S.

The makeover itself begins on Friday afternoon and ends on Monday. Workers may paint or tile or make other physical improvements. Community leaders might cook food for the workers or scrub the windows or whatever else is needed. Equipment is delivered and installed. All over the course of a long weekend.

On Monday, the clinic reopens with a celebration – and a whole new look and feel. And everyone from the service providers to the community members to the patients feel a sense of pride and ownership in the finished product.

“The 72-hour clinic makeover improves the working conditions of the service provider while also improving the experience of clients that visit the facility,” says Dr. Saratu Olabode-Ojo, a senior technical advisor for NURHI2. “It’s a win-win situation from both ends.”

Over the past two years, NURHI has conducted 140 of these clinic makeovers throughout Nigeria’s cities in facilities that offer prenatal and postpartum care and deliver babies. CCP did makeovers in Guinea and Liberia after the Ebola crisis to help restore trust in health facilities there. The Challenge Initiative which, like NURHI, is funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, has just begun some makeovers of its own in Nigeria.

Odengo says the turnaround is felt nearly immediately in every community where a makeover takes place.

“All across the board we have seen an increase in the use of family planning services as a result of these makeovers,” she says. “Renovating the environment makes it more appealing, cleaner and motivates clients to seek care at the facility. It also gives service providers a new sense of pride and meaning about their work.”

After seeing the results of the renovation to the clinic in his Lalkupon community – the new paint and the new equipment – government leader Onolakpo Olayiwola said he was inspired to take it a step further. There wasn’t always room at the Lalkupon clinic for women and children to wait inside when they arrived for services, something the community really needed.

“In order to appreciate the work done by NURHI … we also built-up a waiting area to accommodate our mothers and children when they come to the clinic,” he says.