There is a lot of hype around Artificial Intelligence, or AI.

There is also a lot of optimism around its promise and its application to global health. AI allows humans to do more, faster. But the significant behavior change required to make it useful in our work is something uniquely human.

I recently attended an event at The Aspen Institute in Washington, DC, to launch a new report, Artificial Intelligence in Global Health, Defining a Collective Path Forward. The question that kicked off the day was: Is Artificial Intelligence the Industrial Revolution of global health?

It certainly could be.

The report highlighted 240 real-world examples of AI in global health, with the central theme that “adoption, acceleration and use of technologies should strengthen local health systems and must be owned and driven by the needs and priorities of [low- and middle-income county] governments and stakeholders in order for them to best serve the needs of their populations.”

AI is not the Future, it’s the Now

AI promises to revolutionize all industries – and in many sectors, it’s not the future, it’s the now. Has Facebook ever suggested you tag a specific friend in a photo you just uploaded? That’s a neural network at work – a machine “learning” what to suggest based on measurements of millions of photos of faces.

But what are the implications and way forward for global health? This is the heart of the new report, which contains case studies of AI in practice and the potential for making a real impact on the global health community.

The Communication Component

Many of the AI use cases have communication-related implications. One example describes a Ministry of Health official using predictive analytics to forecast a disease outbreak. It’s important for the ministry of health to possess the information on a potential outbreak from an algorithm, but it is also important to communicate that message to those populations potentially affected. This is where what we do at CCP and AI intersect. Without the right context, the information doesn’t get acted on. Luckily for us, we’re not yet at the point where AI can craft the messages we need.

The Human Element of Artificial Intelligence

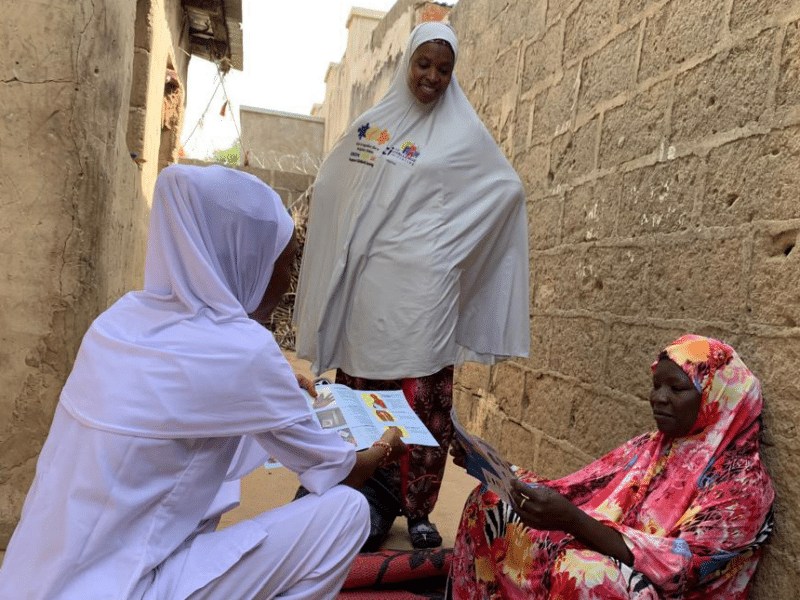

Another case study describes a scenario in the future where a mother in rural Kenya is unsure what to do regarding her two-year old’s fever and rash – travel two hours to the hospital? Wait?

Imagine this mother going to a community health worker, who has an app that uses machine learning to analyze the symptoms, along with a photo of the rash, to determine it’s not dengue, but a much less harmful spider bite. Then, following protocols provided in the app, the worker would also follow up with rapid diagnostic test for malaria, to make sure the fever isn’t something serious.

The possibilities around AI require big thinking and are exciting, but to operationalize this process will require significant behavior change interventions on many levels. Providers need to understand how to use, implement and understand these new tools while community members need targeted behavior change interventions to trust these new technologies. Without their buy-in, AI won’t live up to its promise in global health.

Meanwhile, any AI system needs quality data in order to make accurate predictions or recommendations. For one thing, the new report cites the need for open datasets with “colloquial and formal medical terminology in various languages.” This is a key role for communication professionals who can continually work with communities in low- and middle-income countries to make sure the right data is being collected. If poor or out-of-context data is entered into these datasets, the results will be worthless.

AI is in its nascent stages, and real challenges still exist, such as issues of bias in data. Designers of AI systems need to ensure the predictions the model or machine makes cast a wide net. Consider a dataset of images showing different types of skin rashes. If the images are only from patients in the United States, it would be missing information about rashes that may occur in other parts of the world – a geographic bias that would stand in the way of true progress.

Privacy protections will need to be solidified and significant resources invested. There is also the issue of connectivity and how to gather enough data in a place where computers are not as powerful. AI companies such as Babylon Health are exploring ways for their machine learning algorithm to query large datasets on devices when the connection to the Internet is spotty or nonexistent.

We have a long way to go before we can fully understand all of the ways that AI can improve global health, but it’s exciting to open our minds to the possibilities.

The report was a partnership between USAID, The Rockefeller Foundation and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. The event was livestreamed, and can be watched here.

Marla Shaivitz is the director of digital strategy at the Johns Hopkins Center for Communication Programs.