In 2014, the rate of male circumcision in parts of inland Mozambique was far lower than needed to help control the nation’s HIV epidemic, especially among adolescents and men in their 20s.

Clinics offered the service, but there were not enough takers. And when there were takers, they were not always able to access the available providers.

That’s when USAID, through the U.S. President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR), partnered with the Johns Hopkins Center for Communication Programs to increase demand for voluntary medical male circumcision, or VMMC as it is known. Through a combination of social and behavior change strategies, the number of men ages 15 to 29 in Tete and Manica provinces undergoing circumcision increased nearly five times, from 21,824 in FY15 to 100,636 just two years later, a new USAID case study shows.

“Without the work we did to improve messaging, training, counseling and mobilization, we never would have seen social and behavior change on this scale,” says CCP’s Maria Tanque, VMMC demand generation coordinator for the center’s USAID-funded Communication for Improved Health Outcomes (CIHO) project. “Five years in, we keep building on our momentum, making male circumcision the norm as opposed to the exception in rural Mozambique.”

Since 2007, when the World Health Organization began recommending VMMC in countries with high HIV prevalence and low circumcision rates, more than 14.5 million procedures have been performed for HIV prevention in 14 countries in eastern and southern Africa. Nearly 3 million were done in 2016 alone. The WHO expects more than 500,000 new HIV infections will be averted because of the procedure through 2030.

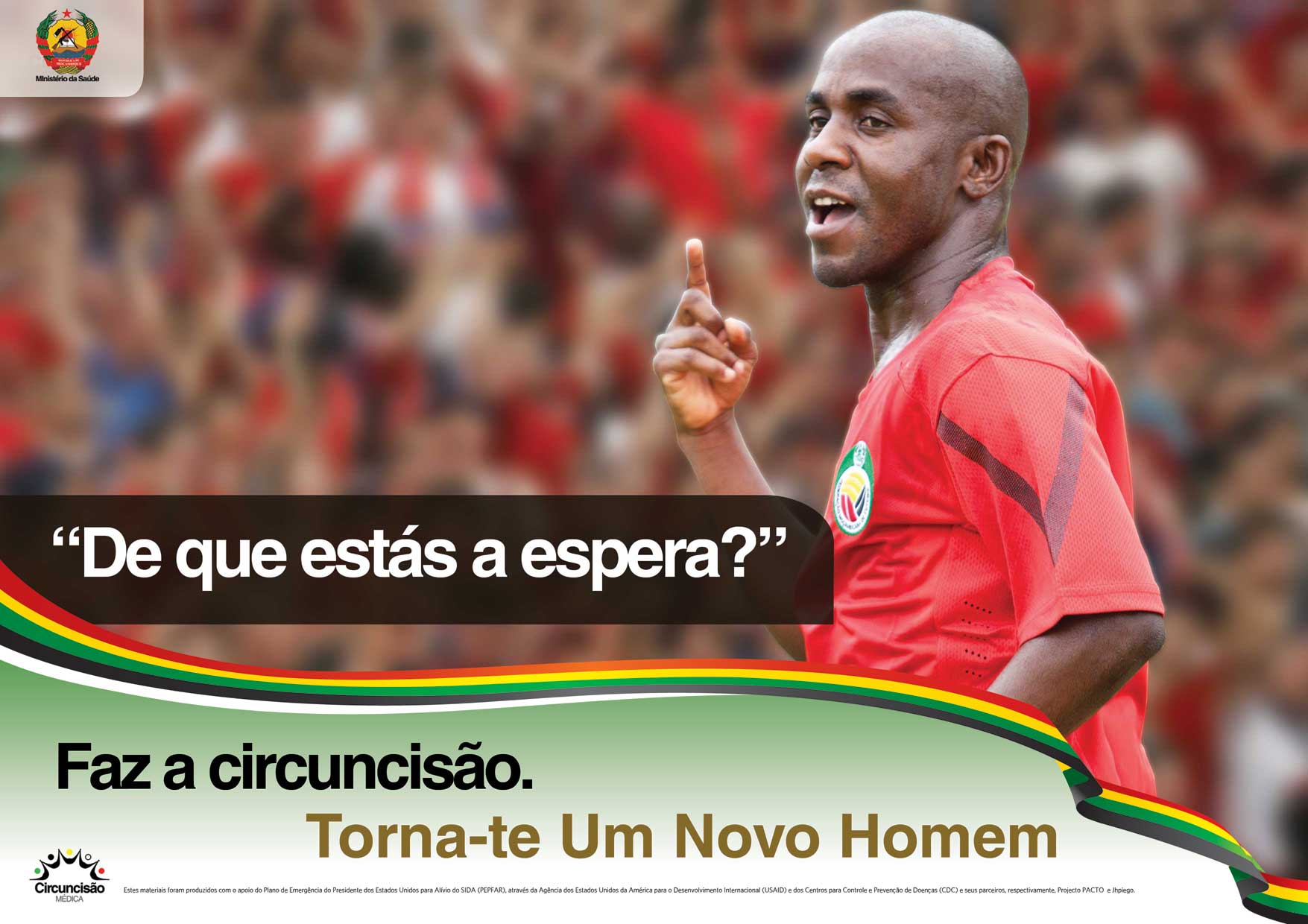

To generate demand for VMMC and help connect men to services, the Mozambique work has been done under the overarching branding “Faz a circuncisão. Torna-te um novo homem,” or “Do the circumcision. Become a new man,” which was based on the findings of formative research conducted by CCP. The Ministry of Health fully adopted it in 2015.

Also key to the effort: personalized client-driven service in clinics, mobile brigades and community spaces, as well as the use of site-level data along with input from clinical partners to make decisions and plan coordinated efforts.

While health officials want to increase the number of circumcisions for health reasons, many of the messages center on the hygiene-related benefits of the procedure which many men find more appealing. To get the word out, CCP not only engaged mobilizers to work directly in the communities but also developed call-in radio programs, trained operators of a VMMC call center hotline, upgraded in-service counseling and communication skills, improved clinic signage, and drafted materials designed to improve provider training and address clients’ specific concerns while highlighting personal benefits.

CCP has targeted not only young men, but their female partners, who they hope will positively pressure the men in their lives to be circumcised.

One ad for the campaign asks, “What are you waiting for?”

The success of the demand generation work in Mozambique, however, had an unintended outcome: Too many people soon wanted circumcision, more than some of the previously underutilized clinics could handle. Some sites had inadequate numbers of staff to meet the new demand, which had led long waiting times.

In response, CCP worked with clinical partners to fine tune the balance between demand and supply, recommending that clinics increase their nursing staff to accommodate more clients and making more providers available at certain clinics on days when demand was higher. CCP also focused communication efforts on clinics with less demand than others.

Being able to continue the program for nearly five years is one of the main reasons why the effort has been so successful, Tanque says. CCP’s experience continues to inform new approaches to increasing demand for VMMC.

Another key element is the personalized support system that mobilizers use to spread the word about VMMC one-by-one in their communities. The mobilizers are able to adapt messages to each person they encounter and earn incentives based on how many people they successfully refer for circumcision. The mobilizers don’t just tell the men they encounter about the procedure; they often accompany them to the clinic and stop by their homes afterward to see how they are feeling.

“I feel proud of what we have accomplished but it’s still not easy to convince men to become circumcised,” Tanque says. “Men don’t usually visit health facilities so it can be a hard sell, especially since those who go in for circumcision aren’t ill. Our best ambassadors are those in the community who have had the procedure and motivate others to do the same. And now we have so many more of them telling their friends and family.”