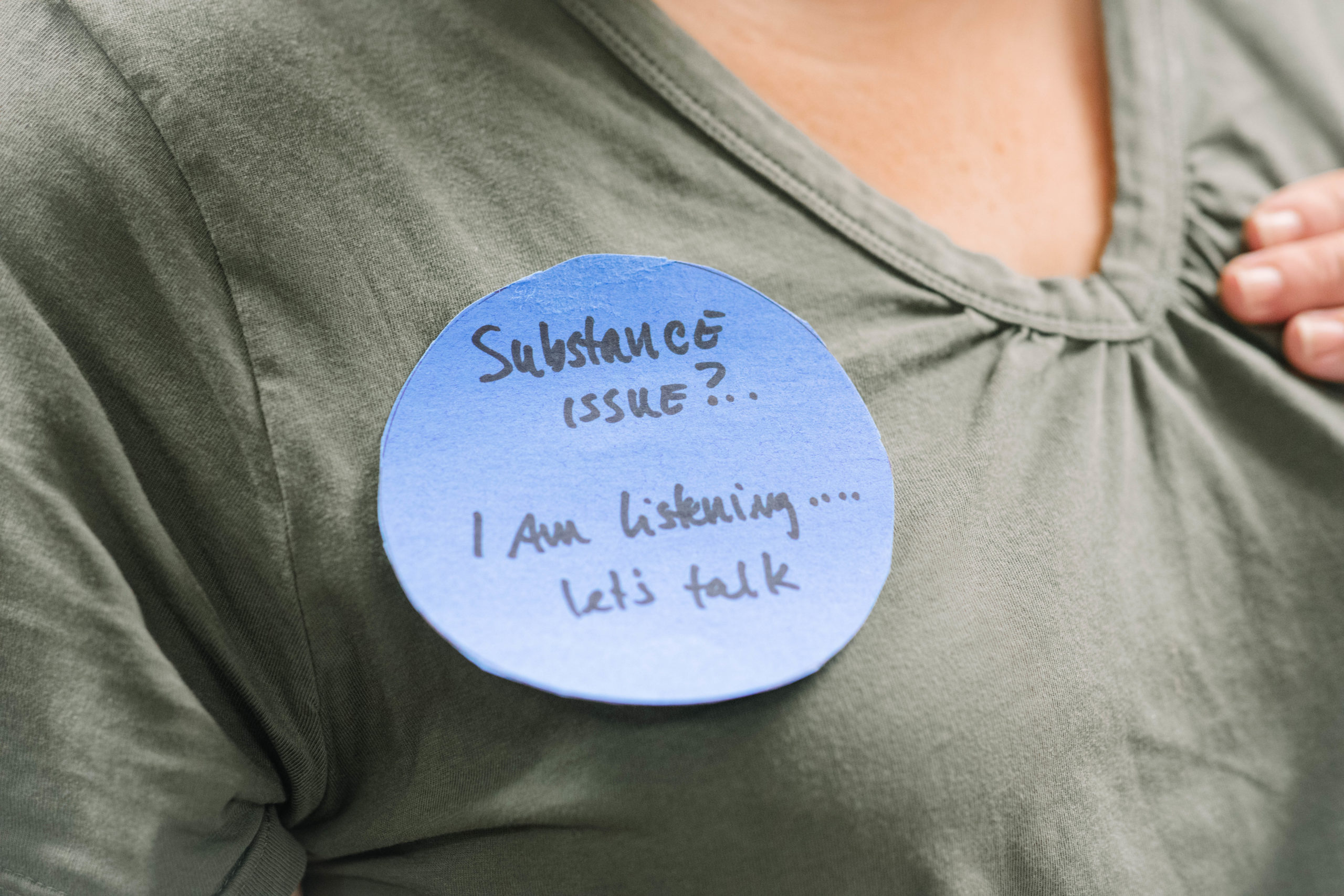

“Addiction issues?” the crudely drawn poster asks. “I’m listening. Let’s talk.”

The stick-figure doctor tells the stick-figure patient: “Opioid use disorder is a treatable condition.”

The messages were just some of many generated over two days this month as part of a “hackathon” led by the Johns Hopkins Center for Communication Programs and the Center for Mental Health and Addiction Policy Research, both part of the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

The goal of the hackathon: To quickly brainstorm ideas for how to reduce the stigma of addiction, in this case among doctors and nurses and others in the health care system. In the midst of a deadly opioid crisis – more people died in 2017 in the United States from overdose than from car crashes – the group came together to find ways to defeat the stigma that keeps people with opioid use disorder from getting the life-saving treatment they need.

“What the science tells us is we have medications that are effective in treating opioid use disorder and are lifesaving, and very few people get them,” said Johns Hopkins’ Colleen L. Barry, PhD, a national expert in addiction policy research.

People who face addiction are often seen as having a “moral failing,” and that’s absolutely the wrong way to think about it, she says. Addiction is a chronic disease that is treatable with FDA-approved medications such as methadone and buprenorphine, which cut the cravings for opioids and allow people to live normal lives. So why is there often such a negative reaction to people using medications to treat opioid use disorder? No one judges people with diabetes for taking their medication. The reason, she says, is stigma.

“We need to change the way we view individuals with opioid use disorder and better communicate that medication treatment works and can save lives,” Barry says.

Two dozen people, including some who are in recovery, gathered from various parts of the health care system to tackle the issue. One of the first people they heard from was Michael Fingerhood, MD, a doctor who treats patients with opioid use disorder at the Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center.

Fingerhood told a story of seeing a patient in her early 20s with HIV. She also had a problem with drug use. He recommended she take buprenorphine. The patient’s mother complained that this would just be substituting one drug for another, a common misperception. The patient rolled her eyes, but it was clear her mother held sway.

Those gathered heard from experts in stigma, who shared data showing that doctors themselves are biased against using medication to treat opioid use disorder and that they themselves use harmful language to describe people with addiction – often their own patients.

“’Addict,’ ‘alcoholic’ and ‘substance abuse’ should not be used anymore,” says Robert Ashford of the University of the Sciences in Philadelphia. “These labels need to be retired.” Other words people hear in the health care setting: ‘junkie,’ ‘dopehead,’ ‘crack addict.’ “There’s no reason to use that language anymore.”

Bill Kinkle, a paramedic and registered nurse, is himself in recovery from an opioid use disorder. His group at the hackathon came up with a series of recommendations for reducing stigma in health care settings. One suggestion of the group was to create a pledge for people to sign, an approach that has been used in other health systems, in which they agree to use appropriate language about opioid use disorder to reduce stigma. The pledge would be part of an education campaign to help improve patient care.

They also suggested buttons that people like Kinkle could wear on the job, if they choose. “I’m a person in recovery,” they’d say. The idea is to generate – and change – conversation.

When people hear he is in recovery, Kinkle says, “they say, that’s amazing. You’re a miracle. But I’m not. I’m one of 30 million. People think that being able to recover is an impossible task. But it’s not. There are a lot of us in recovery, but not a lot of us talk about it.”

The many ideas generated as part of the hackathon will be distilled by people from CCP and the Center for Mental Health and Addiction Policy Research in the coming weeks, with the idea that the Johns Hopkins Health System – and other health systems around the country – can use some of the messages and ideas to reduce stigma and discrimination toward people with opioid use disorder.

“We put in a tremendous amount of work,” Kinkle says. “I’d like to see lives saved and families restored as a result of this.”