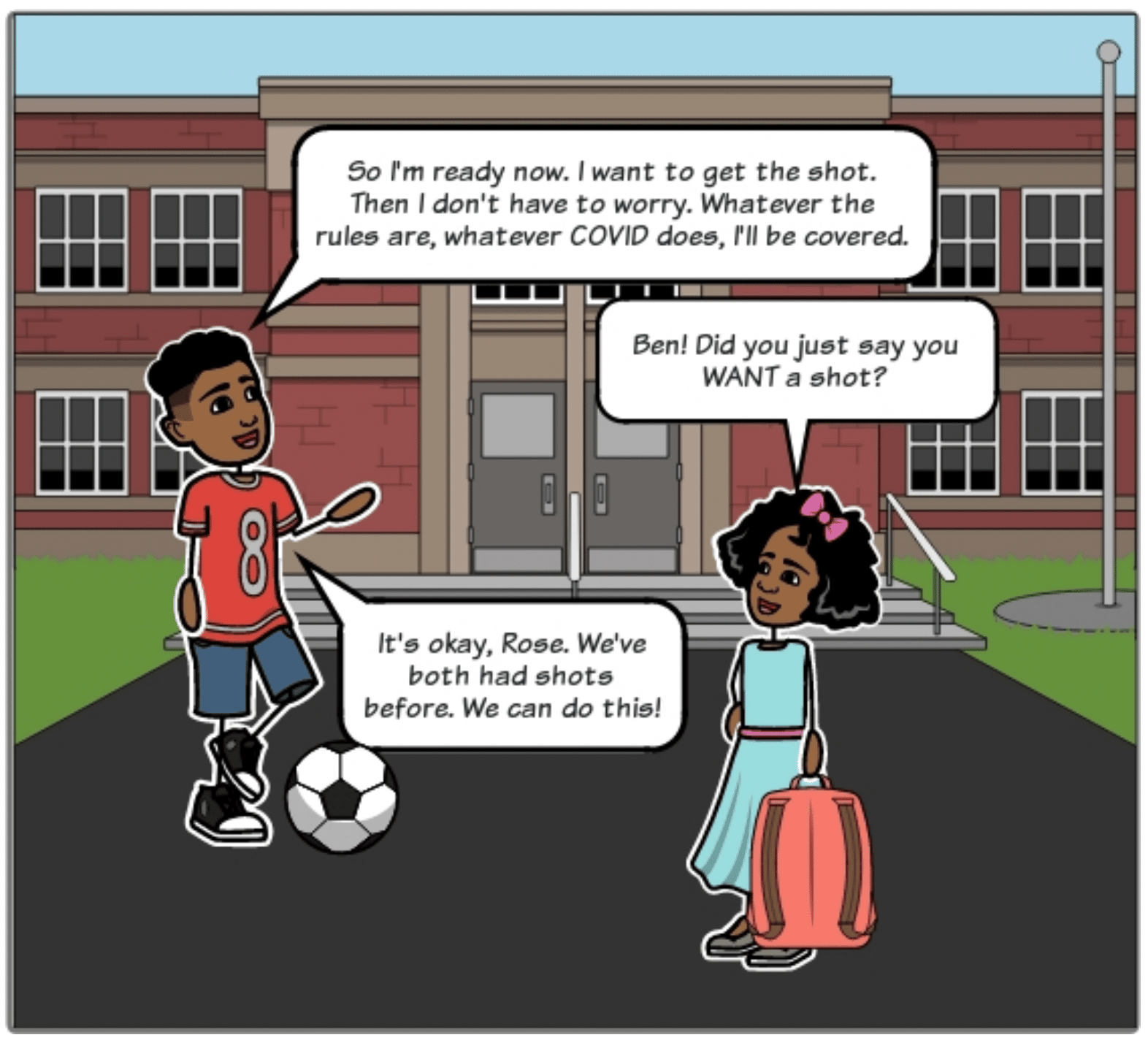

Chatting about the COVID vaccine on their way home from elementary school, colorfully drawn characters Ben and Rose discuss what they’ve been hearing from their parents when they think little ears aren’t listening: Their vaccinated moms and dads are on the fence about providing the same for their kids.

But the kids quickly move on from safety concerns to discussing how they’ve been feeling left out because they haven’t gotten their shots yet. With many organizations requiring vaccines to participate, Ben couldn’t play on his soccer team and Rose had to stay home from a field trip and is missing summer camp.

“There are things I can’t do if I’m not vaccinated,” he says.

Ben and Rose are the cartoon stars of a campaign created by the Johns Hopkins Center for Communication Programs for the Baltimore City Health Department as part of a federal health literacy grant. The latest piece is a story and activity book for “kids and their grown-ups” to use to spark conversations about the pandemic and the role vaccines could play to keep children and others in the community from getting sick.

The book is being distributed to pediatricians’ offices around the city and made available to patients as they sit in the waiting room. CCP staff say they hope the books – and other tools that have already been sent to pediatricians – will create empathy between doctors and parents and make the whole vaccine conversation less fraught.

Vaccination rates lag among young kids, with just 30 percent of U.S. 5- to 11-year-olds fully vaccinated as compared to more than 60 percent of kids 12-17. Vaccines for the youngest children, those six months to five years, were just approved in June.

“The most common comment we get from health providers is literally, ‘This is so adorable’ – that’s the word everyone uses to describe it,” says CCP’s Apral Smith, the project manager on the COVID literacy project. “This book approaches vaccine hesitancy in a non-confrontational way, and this easier message may make parents more comfortable in choosing COVID vaccines for their children.”

For several months, CCP has been developing material for adults – parents, doctors and other members of the community – to help promote COVID vaccines. Now they hope they can reach the children directly. The activity book – with puzzles, games and coloring pages – suggests some questions for parents and their children to discuss after reading the story, including who they should ask for advice as they make their decision.

“Having children engaged in this conversation can make it less mysterious, less scary,” says CCP’s Amber Summers, who leads the Baltimore portfolio. “Kids have been listening to adults talk about COVID all this time. They’ve been absorbing this information to whatever degree they are able. Hopefully this can ease their concerns – and their parents’ too.”

The idea of the book came from work CCP has done with Baltimore health providers to improve vaccine uptake. CCP created a toolkit to help providers have conversations with parents about the reasons to get vaccinated against COVID and also fact sheets and other resources for parents. The doctors told CCP they wanted something to give to families to read in their waiting rooms, primarily because while the decision to vaccinate against COVID isn’t the child’s to make, they will be impacted by it.

“That evolved into telling the story from the child’s perspective,” Summers says. “Talking about things that parents are concerned about – actually saying them out loud – remind them to have these conversations with their children as well as their trusted health care provider.”

Another book is in the works to talk about COVID with Ben and Rose for back-to-school time.