As in many other countries, the people of Uganda lived under lockdown during the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, many unable to work and make money to feed their families as the new disease raced across the world.

Now, in some parts of Uganda, lockdowns have again become a fact of life. This time because of Ebola.

Since the first Ebola cases were identified in September in central region of Uganda, there have been 142 confirmed cases and 56 associated deaths in the country. The districts of Mubende and Kassanda had been under Ebola-related lockdown since Oct. 15, which was just lifted over the weekend.

Given the current health crisis, the Johns Hopkins Center for Communication Programs-led Social and Behavior Change Activity (SBCA), in collaboration with Uganda’s Ministry of Health and other stakeholders, developed social and behavioral change interventions to address gaps identified, myths and misconceptions and promote behaviors and practices to encourage prevention of Ebola Virus Disease.

SBCA is also supporting the coordination of the risk communication and community engagement (RCCE) response, taking on roles in message development, social listening and evidence generation, and on national sub-committees. Supporting the Ministry of Health, SBCA has also worked to adapt existing Ebola risk communication interventions and develop new ones to address the emerging realities of the current outbreak.

But the messengers are facing one major obstacle: Many Ugandans are so fatigued by the COVID-19 restrictions of the past few years that they are reluctant to believe that another health crisis is upon them, which increases the risk that people won’t follow preventive advice.

“The community feedback has been, ‘It cannot be happening right now,’” says CCP’s Catherine Kanyesigye, the technical specialist for COVID-19 and emergencies for SBCA. “There’s a general sense of, ‘Are you sure this is a thing?’”

Ebola can be transmitted through direct contact with an infected animal (bat or nonhuman primate) or through the bodily fluids of someone who became sick or died from the virus. It often begins with “dry” symptoms such as fever, headache, aches, sore throat and fatigue and then gets progressively worse with “wet” symptoms, such as diarrhea, vomiting and unexplained bleeding. The case fatality rate for this outbreak is around 39 percent, meaning that 39 percent of those who contracted the disease have died.

The messaging is about the importance of preventive measures: Avoiding contact with blood and bodily fluids (such as urine, feces, saliva, sweat, vomit, breast milk, amniotic fluid and ) of people who are sick. Avoiding sex with men who have recovered from Ebola, until testing shows that the virus is gone from his semen.

Another key: In order to reduce the potential spread of Ebola, it is crucial to report suspected cases to health authorities immediately, and for individuals to call for help at the nearest health facility immediately they start experiencing symptoms of Ebola.

Evidence received by the Ministry of Health and the World Health Organization has shown that those who begin treatment as soon as they develop Ebola symptoms have a high chance of survival.

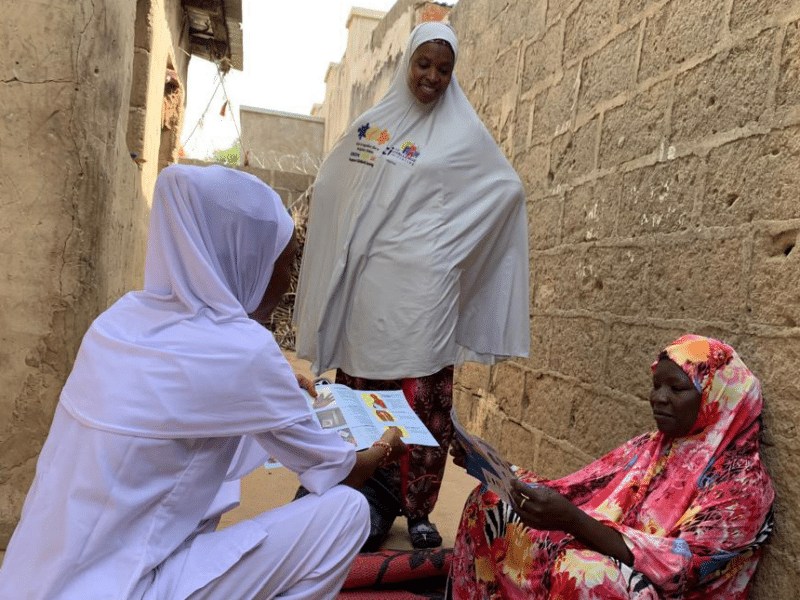

The messaging also includes engaging mass media to promote Ebola awareness, helping create up-to-date content and designing and disseminating Ebola materials and tools to partners and target audiences. The project is also working with local communities to promote preventive behaviors and practices at household level and rumor tracking and management.

The virus circulating in Uganda is the Sudan strain of Ebola, for which there is no proven vaccine, although there are several candidate vaccines heading toward clinical trials. Kanyesigye says.

In Uganda, when people don’t feel well, the majority’s first visit is typically to the traditional healer. According to the health ministry, more than 60 percent of Ugandans rely on these healers to handle ailments. If someone comes in with Ebola, such visits could expose larger numbers of people. So, the messaging is report cases immediately to the health authorities.

The greatest fear, Kanyesigye says, is the spread of Ebola in Kampala, Uganda’s capital city, and other densely populated districts.

Recently, SBCA engaged imams in the five divisions of Kampala. Cultural and religious burial practices are extremely high risk activities because transmission of the virus is particularly virulent at the time of death. When someone dies of Ebola., safe and dignified burial teams must be called to safely remove and process the body for burials.

“We have to do everything we can to curb the chain of transmission, especially since containing Ebola in a heavily populated, urban city like Kampala is complex,” she says. “If it happened in one neighborhood, it would spread like wildfire, and increase burden on the health care system as well as negative economic impacts especially through restricted movements and lockdowns.

“That’s why these risk communication is crucial in times such as these. Empowering communities to cooperate and avoid further spread of the disease is paramount. Additionally, collaborative efforts from all partners in the response is Uganda’s best shot at ending the outbreak.”