Five years ago, not long after fentanyl became a deadly additive to street drugs in Baltimore, the Johns Hopkins Center for Communication Programs hosted a three-day hackathon, bringing together community leaders, health officials and people who use drugs to develop a strategy to reduce opioid overdose deaths.

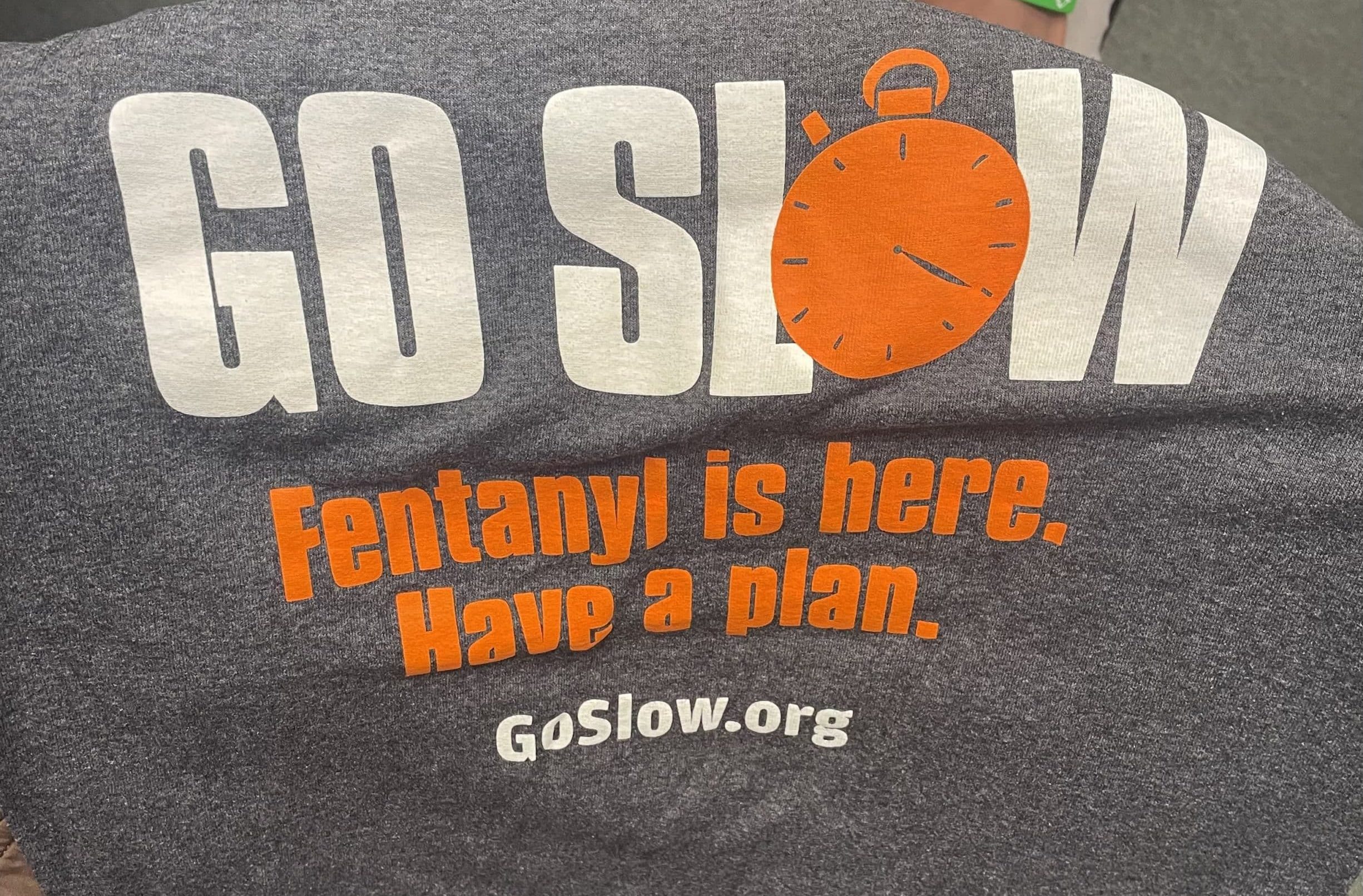

Those messages were shaped into the “Go Slow” campaign and became an on-the-ground effort led by Bmore POWER, directing people to a website with resources for people who use drugs. The message is three-fold: Go slow (when injecting drugs). Never use alone. Carry naloxone (the overdose-reversal medication).

While the campaign gained traction — and the website is still maintained with private funding — the opioid overdose crisis in Baltimore and around the state and nation has since reached record highs. Overdose deaths in Maryland have nearly doubled since 2015 in non-Hispanic whites, while Black deaths have risen three-fold and Hispanic deaths five-fold. People 55 and older is the largest age group for overdose deaths, says Aleah Robinson of the Maryland Department of Health.

“Behind these numbers are human lives,” says CCP’s Tina Suliman, a senior program officer who mainly focuses on Baltimore. “There are people we love, community members in these numbers.”

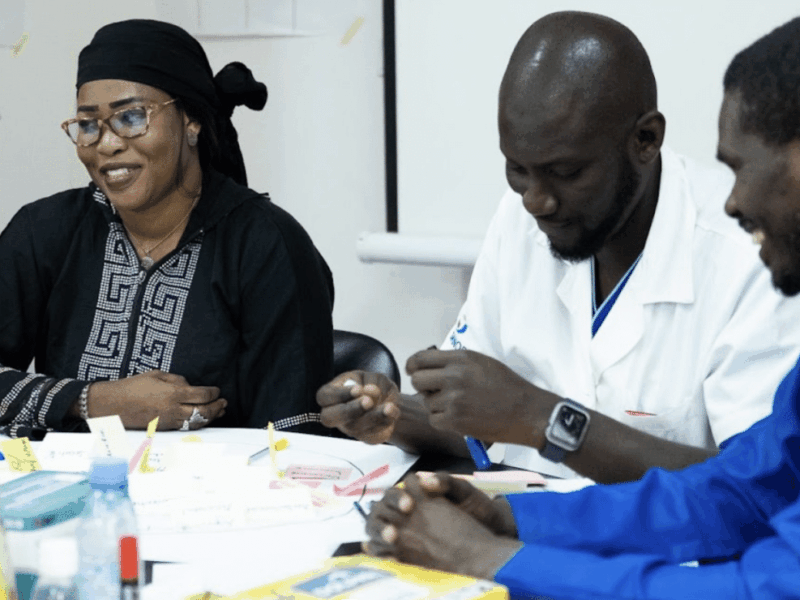

In January, CCP held another three-day hackathon, sponsored by the Department of Health, focusing on ways to better train counselors and others in Baltimore to talk to Black and Latino people who use drugs to reduce their risk of overdose and get them help.

The ultimate goal is to create a campaign using a harm reduction lens to reduce racial disparities in overdoses by countering the death and destruction being caused by the opioid epidemic among Black and Latino communities in Maryland. “Each person brought their strengths and expertise to the table, which is necessary to develop messaging that is meaningful,” says CCP’s Apral Smith, project manager on the opioid harm reduction effort.

Attendees spoke openly about the struggles they and others have had in trying to no longer use substances and stay in recovery, and helping others do the same. One woman spoke of her decades long struggle to stop using drugs. In recovery now, she says she often doesn’t even know how to live a productive life. “I used up all my time on drugs,” she said. “I don’t even know what kind of work I can do.”

Said Joy Barnes, who works on overdose prevention for Baltimore City Department of Health, as she tried to encourage her seatmate: “Every day above ground is a good day.”

Another woman spoke of starting to drink alcohol at the age of eight – her father giving her beer to drink at family crab feasts – long before she was educated on the risks of what became a gateway to long-term drug use.

The participants spoke about the concept of harm reduction, about the impact of systemic racism on the lives of Black people, about how they might convince their peers to take steps to prevent overdose and how to guide them through the process.

Soon, the participants broke into small groups to develop their own ideas, using human-centered design techniques to brainstorm solutions to the problem. With hundreds of colorful sticky notes and giant pads of paper, they delved into the barriers that keep messages from getting through to the people who need to hear them and discussed just who they were trying to reach.

The most moving part of the three days came toward the end, as Suliman gathered the group in a circle. With bowed heads, she asked everyone to say aloud the name of someone in their lives who had been lost to the opioid epidemic.

“Miss Gloria …. Miss Brenda … Will Sr. … Great Grandma … Mo … Cheeky,” came the names, one by one, and everyone in the circle solemnly repeated them.

“They matter,” Suliman told those assembled. “They’re part of this work.”