Knowledge management (KM) is the process of sharing and using experiences and evidence to solve pressing problems. This is especially important when resources are limited, people work in different locations, and we need knowledge that fits the situation to make informed decisions for policies, programs, and practices.

Suppose you need to make the case for continued commitment and funding for your country’s reproductive health programs, at a time when fertility rates are declining and national leaders are questioning the need for a focus on family planning. Having a high-quality knowledge management strategy in place, including access to the latest evidence and being able to learn from other country FP programs how they have garnered continued support for FP, could make the difference in maintaining a range of contraceptive options and services for women and their families. In fact, this was a real-life situation for Nepal’s family planning subcommittee.

The Johns Hopkins Center for Communication Programs has a long history of being a thought leader in knowledge management. We draw on this expertise to make knowledge management easy, attractive, salient, and timely through projects such as the USAID flagship Knowledge SUCCESS project. We also play key roles in supporting the overall health and well-being of young people in the PROPEL Youth & Gender Project, advancing global understanding of health and population trends around the world in the Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS) program, and scaling up successful family planning programs in Nigeria through The Challenge Initiative (TCI).

The key to a successful KM program, we have learned, is to never sit on our laurels. We are continuously developing new, creative, and inclusive ways to improve this very important work. As we step into the new year, here are three major themes driving our work.

1. Normalize failures

Have you ever failed at something? For most of us, the answer is yes. We’ve been in situations where our results do not meet expectations. Yet, we work in an environment where sharing failure is fraught. We avoid talking about failure, and fear repercussions ranging from reputational damage to loss of funding.

CCP imagines a world where talking about failure is encouraged, and programs can learn as much from what doesn’t work as what does. We’ve undertaken a transformational effort to foster a culture of failure sharing among family planning and reproductive health (FP/RH) professionals around the world. Through Knowledge SUCCESS, this has included hosting a high-profile “fail fest” during the 2022 International Conference on Family Planning. Our work has shown that it is possible to embrace failure, especially when we invoke behavioral economics concepts like gain-framing that highlight positive aspects such as learning from failures. Similarly, CCP’s work leading the KM and learning portfolios for the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation-funded TCI project used pause and reflect (P&R) sessions and most significant change to assess what has worked and not worked. Using the P&R technique, TCI was able to adjust its coaching model – from its initial conception of an on-demand coaching model to the Lead, Assist, Observe coaching model, which provides more proactive coaching in family planning and reproductive health to TCI city teams at the beginning and gradually decreases the level of intensity as implementation progresses and teams gain confidence.

2. Practice “knowledge marketing”

Have you tried to walk in the shoes of your audience? We’ve looked at the processes and behaviors that global health workers go through on a daily basis when looking for information and realized it’s very similar to a customer journey, a well-known concept in business that maps an individual’s path to purchasing products and services. It starts with someone becoming aware of their need for information (which is like a product), searching for information, reviewing the results, considering whether a resource is a good fit, and finally deciding to use it.

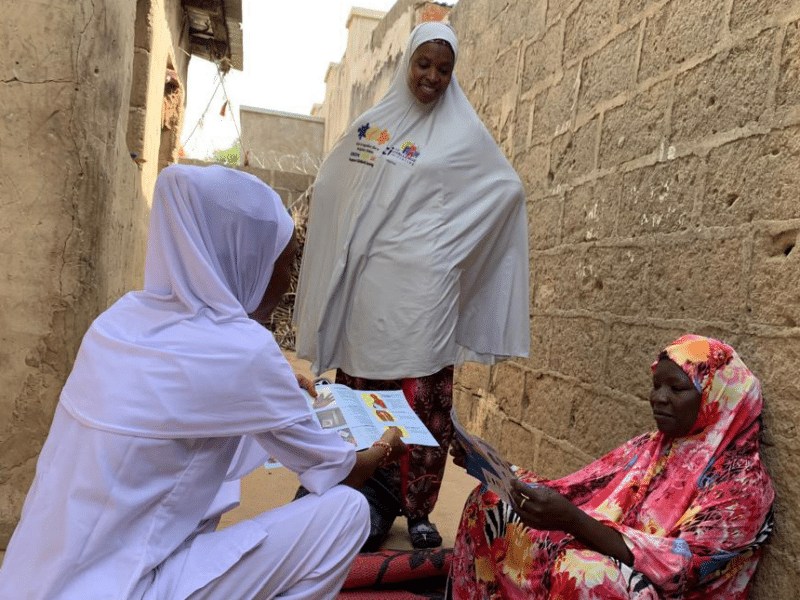

CCP has developed a new approach, called “knowledge marketing,” that helps us conceptualize technical knowledge and evidence as “products” that meet peoples’ needs, and design and promote these products in a way that ensures people will use them and recommend them to others.

Knowledge marketing recognizes the need to consider global health and development workers as individuals, rather than only by their professional roles. Competing priorities, personal lives, culture, location, and identity may impact their opportunities to access and act on information. At a time when global health work is experiencing a decolonization movement, it also reconfigures the balance of power. By placing community members in the role of the “customer” or consumer, we are prioritizing their needs in context.

3. Design with equity in mind

At CCP, we define equity in KM as the absence of unfair, avoidable, and remediable differences in knowledge access, creation, sharing, and use among groups of health workforce members, whether those groups are defined socially, economically, or environmentally. As we embark on KM initiatives, we consider four essential aspects: availability, accessibility, acceptability, and quality.

We use a Checklist for Assessing Equity in Knowledge Management Initiatives. As a partner on the recently-awarded PROPEL Youth & Gender project, CCP is working with the International Youth Foundation and other partners to design activities with equity in mind. As the project’s advocacy lead, we draw on many of our equity in KM principles to ensure that youth and people of all gender identities are included in every step of the project’s design and implementation. Accurate, timely data is also essential. As the KM partner for the DHS Program, CCP helps collect and disseminate data in population, health, HIV, and nutrition through more than 400 surveys in more than 90 countries. Robust data availability and accessibility, including 25 years of free electronic dataset distribution, have helped establish the DHS Program data as the “gold standard” to inform national, regional, and global policies and programs.

And we are now strategically using AI-powered tools in support of equity efforts. For example, many technical resources are available only in English and, for people for whom English is not their first language, listening to content can be easier than reading it. We use AI technology to produce audio content and translate videos into other languages, such as French. This isn’t to say that all AI will solve all of our challenges. As we know, there are also downsides to the rapidly evolving technology, such as the risk of spreading the wrong information. But we are committed to using every tool we can find so that more people around the world have access to the tools they need to improve their lives.

As you embark on your KM work, consider how these three elements (sharing failure, marketing knowledge, and designing with equity in mind) can enhance your practice. We find that this allows us to reach more people with the information they truly need, in the way they need it, so that they can place it into action within their organizations and programs. As the year progresses, we will be watching closely to see what else 2024 has to bring.

Tara Sullivan is director of knowledge management at CCP and director of the USAID-sponsored Knowledge SUCCESS program. She teaches the Knowledge Management for Effective Global Health Programs at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.