Ensuring children in Nigeria and other low- and middle-income countries have a balanced diet of nutrient-rich foods has long been a challenge, but new research suggests that retraining community health workers (CHWs) to emphasize empathy and true dialogue in conversations with caregivers could improve nutrition outcomes.

Insufficient nutrient intake from the critical ages in the early months and years of life can irreversibly harm a child’s rapidly developing body and brain. Globally, only one third of children aged six to 24 months are fed the minimum number of food groups to achieve dietary diversity. Children’s dietary diversity and health is directly affected by access to safe, affordable, varied foods; adequate care; and quality maternal and child health services.

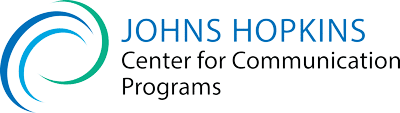

New research, led by the Johns Hopkins Center for Communication Programs, was published January 2 in the journal Health Promotion Practice. CCP led a human-centered design process to understand the barriers to feeding infants and young children with a healthy diet.

The CCP-led work took place in three Nigerian states – Kebbi, Ebonyi and the Federal Capital Territory.

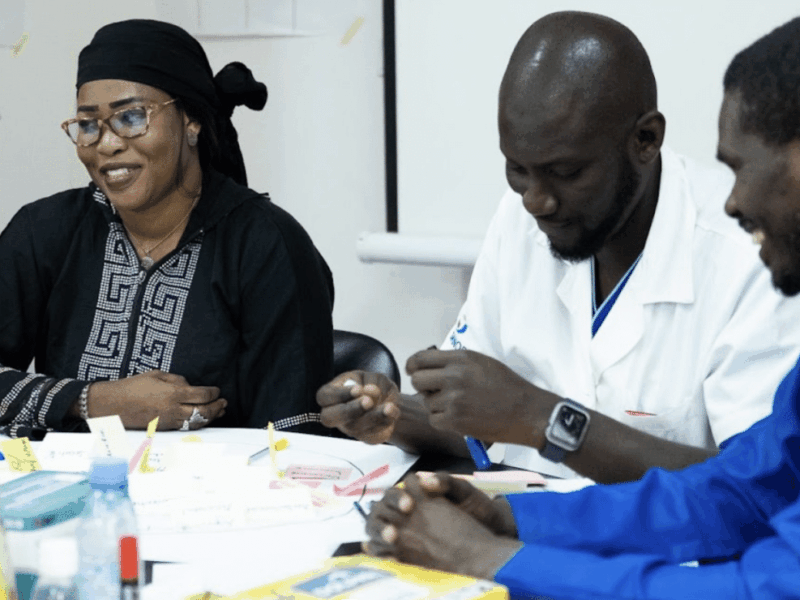

A key insight came from Kebbi, where researchers learned that many caregivers do not value CHW counseling, likely due to a lack of connection or trust, combined with one-way, information-heavy messaging.

The caregivers felt that these interactions did not always provide them with enough opportunities to voice their needs, ask questions, or address their most pressing challenges.

“The whole process revealed that clients, caregivers, households, often feel that when CHWs visit, they are just talking at them, instead of with them. There isn’t often trust built, and many don’t really find these sessions all that useful,” says CCP’s Lynn Van Lith, who worked on the project. “What we try to do instead is transform the interaction between the CHW and the caregiver to make the interaction far more of a dialogue, rather than one-way rote memorization and regurgitation of messages.”

Through this application of human-centered design in Nigeria, the team was able to identify and better understand challenges to practicing priority nutrition-related behaviors and to co-create, rapidly test, and validate potential solutions. The result was a simple tool that encourages interactive conversations and empathy.

“This is so that when CHWs get to a household, they don’t just run through the litany of messages, but instead they ask a few questions, such as, ‘What are the things that you’re struggling with?’” Van Lith says.

“Then they adapt the conversation to address the caregiver’s concerns. The other important insight that we incorporated into this tool is that if a CHW shares some of their own experience, as simple as saying, ‘Yes, I understand where you’re coming from. When I had my son, I had the same struggle.’ That empathy, that shared space and understanding helped the caregiver accept a little bit more what the CHW was saying and take that to heart.”

After making these straightforward fixes, Van Lith says, CHWs, caregivers, and community influencers found the tools fostered connections, promoted open dialogue, and enhanced the quality of counseling.

One community health worker told researchers that “it has never been so easy to talk to them [caregivers].” After using the new approach, the health worker reported, “they talked a lot.” Caregivers also enjoyed and learned in the sessions. One caregiver even noted: “That is the first session that I think I will remember what was said.”

While each human-centered design process is unique, the need for human connection is universal, the authors of the study write.

“The success of the counseling prototypes that allowed CHWs to take a step back from ‘delivering information’ and create space to listen and build a two-way connection is something that could have wider implications,” the researchers concluded. “This approach facilitates a new dynamic in CHW counseling that encourages empathy and allows caregivers to speak freely about their specific needs and questions. This in turn allows the CHW to focus the counseling session on what the individual caregiver in front of them needs most, rather than wasting time delivering irrelevant content.”

Van Lith says that the same approach can be used beyond nutrition programs.

“The simplicity of it is, where the beauty lies, is that magic can happen when you actually connect with someone and have a meaningful conversation about any health-related topic,” she says. “In this case, it’s around infant and child feeding. But the whole point is that this kind of work is relational, and we need to pay more attention to that instead of repeating messages that don’t really land with people.”

“Lessons Learned from the Use of Human-Centered Design Approaches to Improve Nutrition in Nigeria” was written by Amelia J. Brandt, Lynn M. Van Lith, Nokafu K. Sandra Chipanta, Lisa Sherburne, Kizzy Ufumwen Oladeinde, Angela Samba, TiaSamone Haygood, Chizoba Onyechi, Eno’bong Idiong, Sammy Olaniru, Amina Bala, Gloria Adoyi, Justin DeNormandie, J. Douglas Storey, and Shittu Abdu-Aguye.