How are Black boys and men doing? The Brookings Institution – with the help of the Johns Hopkins Center for Communication Programs – is trying to take the temperature of the community and create systems and environments where they can thrive.

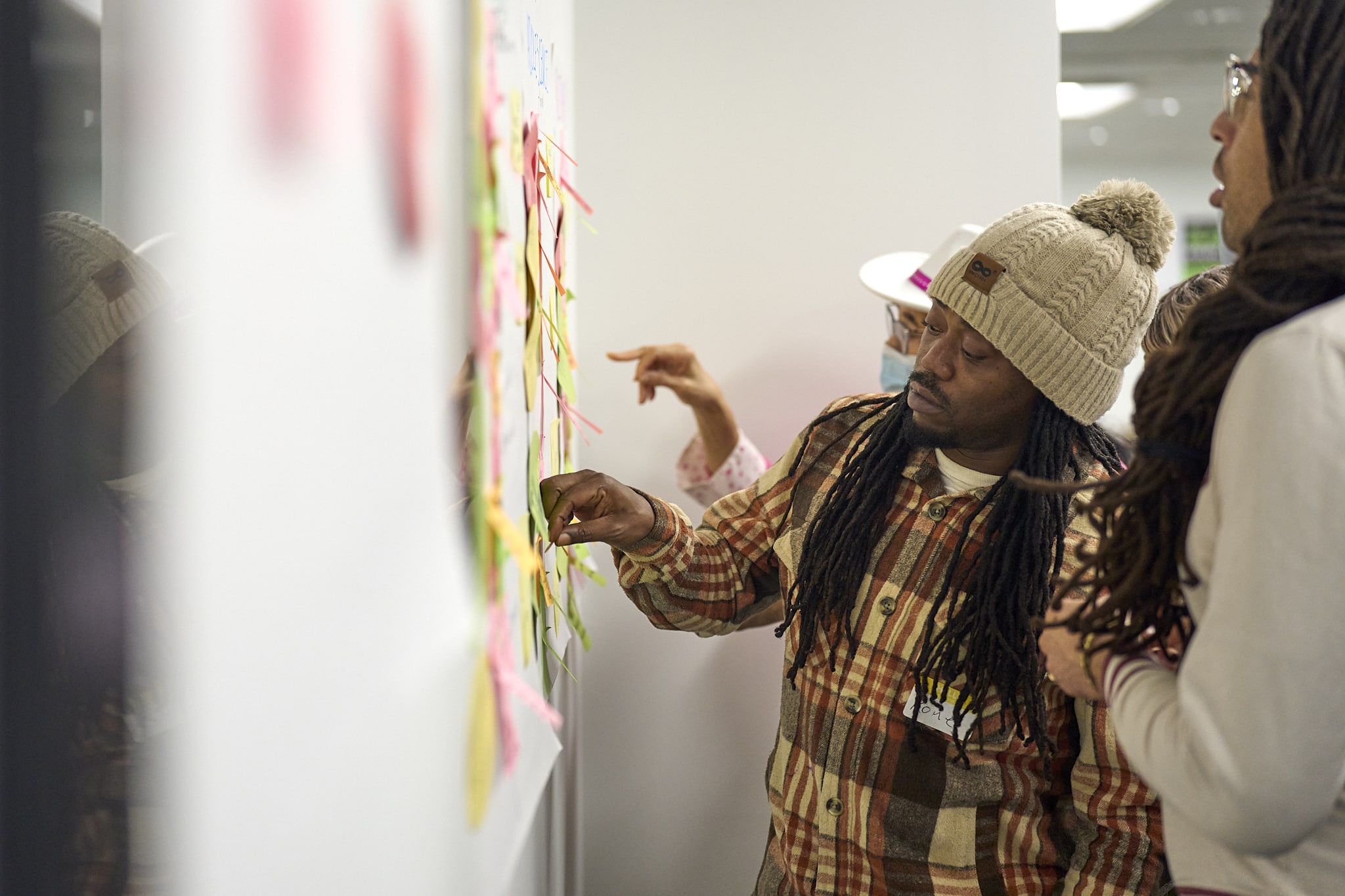

At a community conversation last month in Baltimore designed to help create a definition of well-being from the voices of Black men and women, CCP listened as people shared their lived experiences – and shared the kind of stigma that often holds Black men and boys back from being their best selves, while identifying narratives and strategies to create change. Conversations in Montgomery County, Maryland, and Little Rock, Arkansas, co-created with the Brookings Institution, will allow facilitators to explore well-being from Black men’s perspectives in multiple locations.

In Baltimore, community members spoke about a perception that Black men must be stoic and tough, an expectation that they would respond with anger or aggression – and how there is great value in defining both well-being and Black masculinity by embracing their emotions and taking care of their mental and physical health.

“We developed the project with the idea of asking communities to define, describe and characterize well-being for their communities, broadly, and more specifically for Black boys and Black men,” says Keon Gilbert, a fellow in governance studies at the Brookings Institution.

“We want to use those definitions, concepts and ideas to think about ways that we can develop tools for assessment, accountability and policy. And we recognized, after looking at previous studies and previous projects of well-being in the U.S. and abroad, that one of the biggest pieces that was missing was community voices and projects being community driven. That’s the gap we are trying to fill.”

His colleague, Camille Busette, vice president of governance studies at Brookings, said that there is a norm around Black men and boys being self-sufficient which can lead to feelings of isolation. “It’s driven by the realities of dealing with racism, but it can have the impact of people being cut off emotionally not only from their own way of managing their emotions but also cut off mostly from other people, which isn’t good for well-being,” she says.

The workshop in Baltimore was modeled on a series of similar workshops that CCP has led on issues from the fentanyl crisis to addiction stigma to the challenges of young fatherhood. These events have brought together community members, stakeholders, and experts to co-design solutions, ideas or definitions. They are dynamic and interactive events designed to rapidly generate creative and practical outcomes through dialogue, mutual understanding, and collaborative creativity.

August Summers, director of CCP’s domestic initiatives, looked around the room during the recent workshop. “We are here to speak to men who represent different experiences, to bring in their perspectives about what well-being means for them, what well-being means for our brothers, our fathers, our sons,” he says. “We want to explore solutions that set up environments and support systems to help Black men and boys thrive within our communities.”

Jay Wilson is 28 and is director of operations at a local mental health organization. He joined the workshop because he believes there is a need to shape social norms, especially around safety and vulnerability of Black men.

“You can have all the resources in the world, but if being emotional and vulnerable is not normalized, not made to be a masculine thing, not made to be an acceptable thing, no one will use them,” he says.