The Somali Imam stood up at the end of a weeklong workshop meant to develop ways to promote birth spacing in the conservative nation. He told those gathered that he had always aspired to have at least 20 children.

Though he hadn’t given the topic much thought before, the Imam found himself listening intently as the facilitators and fellow religious leaders spoke. They discussed the concept of tanzīm al-nasl – birth spacing – and how allowing two years between pregnancies is not only beneficial for the health of the mother and child but also supported by Islamic principles.

He was struck by how this guidance aligned with the Islamic emphasis on compassion, responsibility and the well-being of the family. It became clear to him that promoting birth spacing was not just a matter of health. It was a matter of faith. Now, he understood; it was their collective duty to carry this message to their communities.

“My perspective has changed,” he said. “I now plan to have a thoughtful conversation with my wife about child spacing, so that we can raise a healthy, happy family together.”

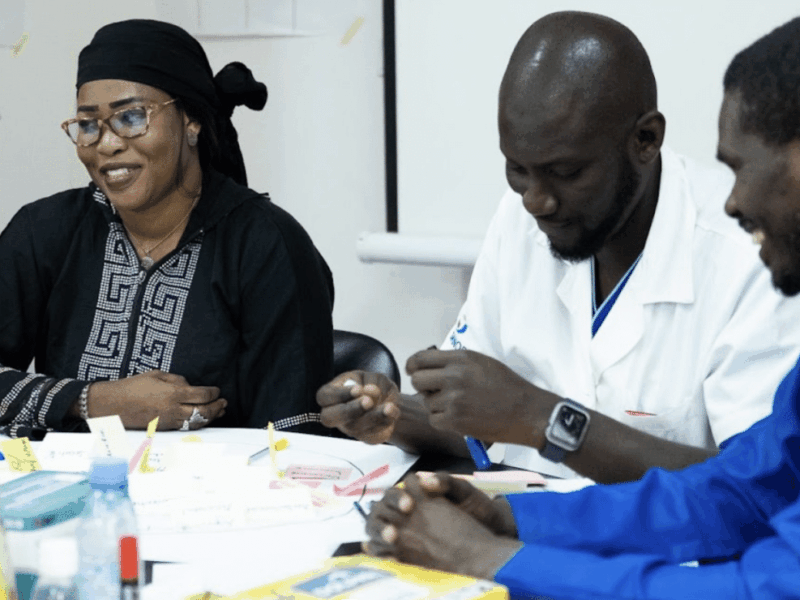

In May 2025, the Imam participated in a one-week social and behavior change capacity building and campaign message co-creation workshop in Mogadishu as part of the WISH2 project. The project seeks to empower women and adolescents, particularly those who are poor and most marginalized, to have a greater voice, choice, and control over their sexual and reproductive health and rights.

The group’s 20 participants included senior health ministry officials, Muslim scholars, an official from Benadir University in Mogadishu, people with disabilities, local organizations and more, working alongside staff from the WISH 2 project.

The Johns Hopkins Center for Communication Programs is a key partner in the project, funded by the UK Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) and led by the International Planned Parenthood Federation (IPPF). It is being implemented across seven countries: Burundi, Ethiopia, Madagascar, Somalia, South Sudan, Sudan, and Zambia.

In Somalia, WISH 2 focuses on increasing knowledge and shifting attitudes and negative social norms. CCP recently provided technical support to the Somali government and partners in the co-design and implementation of activities, working closely with other partners – the International Rescue Committee (IRC) and Ipas – to strengthen community and provider behavior change.

To ensure cultural and contextual relevance, the social and behavior change approaches and key messages in the Somalia workshop were pretested with representatives of community stakeholders, including young married people, men, religious leaders, people with disabilities, and women who represented the interests of mothers and mothers-in-law.

While some social norms are often influenced by misleading interpretations or misunderstood cultural and religious practices, change is gradually taking root, especially among young adults, when it comes to freedom of expression and decisions pertaining to child spacing and family issues, says CCP’s Alfayo Wamburi, a regional senior social and behavior change advisor for the WISH2 project. This is especially true when it comes to the concepts of gender roles and individual agency, he said.

“This project presents a unique opportunity to address related social norms from an Islamic perspective,” he said. “Co-creating social and behavior change materials with Islamic leaders can integrate key messages into their daily community engagements. Tailored content can target young married couples through platforms such as universities, colleges, mosques, and religious gatherings.”

Invited to contribute his experiences and perspective as a person with a disability, Mohamed Omar Khalif said that he has often been treated as someone fully reliant on others for survival. When he first arrived at the workshop, the same thing happened: “They saw me as someone who was incomplete, pushing me around like a wheelbarrow whenever they offered help, and constantly interrupting me when I tried to contribute.”

But as the training progressed, and participants were part of conversations about how messages could be tailored to those with disabilities, Khalif saw a change.

“When offering support, they talk to me, inform me about staircases or obstacles ahead, and listen attentively to what I have to say,” he said. “They now understand that I have no limitations apart from my disability.”

This translated into the work, Khalif said. “We are making sure that persons with disabilities are included, not just in words, but with specific messages tailored to us,” he said. “This kind of inclusion is something you rarely see in Somalia, and it makes me very happy,”

The creation of materials and radio spots at the workshop was done with the specific cultural and social norms of Somalia in mind. The focus was not on contraception specifically, but the benefits to mother and child when births are planned and properly spaced.

“This is the best approach to engaging the community,” said Abdulkhadir Wehliye, a senior advisor at the Ministry of Health in Somalia, who participated in the workshop. “In the country, it has been common practice for materials to be downloaded from the internet, often using images from other countries, which did not reflect our local context. As a result, most of them were ineffective and did not create impact. … I am confident that messages developed will be well received by the community and will contribute to the social norm change envisioned by the program and the government.”

CCP’s Wamburi said there was sometimes an internal conflict at the workshop among religious leaders regarding the need for birth spacing and certain Islamic teachings that emphasize having many children.

One of the participants, Sheikh Hassan, quoted the Koran’s teachings on fertility and breastfeeding.

“Our communities need both healthy mothers and healthy children,” he said. “Birth spacing helps achieve that, and it aligns with Islamic principles of compassion, balance, and care. However, the concept of family planning, which often involves limiting pregnancies and the number of children, is complex and some believe it contradicts our religious values and teachings. So how do we, as religious leaders, reconcile these two important considerations?”

These conversations guided the SBC messages development process for different target audiences to provoke and stimulate dialogue at community level. These messages with the tagline “A healthy family is a healthy community” (Qoys caafimaad qaba waa bulsho caafimaad qabta) will be disseminated through national radio, posters, social media, street banners, and interpersonal communication, targeting young married couples and their influencers.