The biggest barrier to increasing the use of modern contraception in rural Ethiopia may be the expectation in many communities that each woman should give birth to four or five children, new Johns Hopkins Center for Communication Programs research suggests.

The finding offers clues to why it has been so challenging to increase rates of contraceptive use in the country. While researchers expected there to be reluctance to child spacing, they were surprised it only began to wane after that many children were born. They also found that the pressure of social norms led many women to give birth in the first year of marriage.

Giving birth to children less than 24 months apart has been linked to health risks to both mother and child.

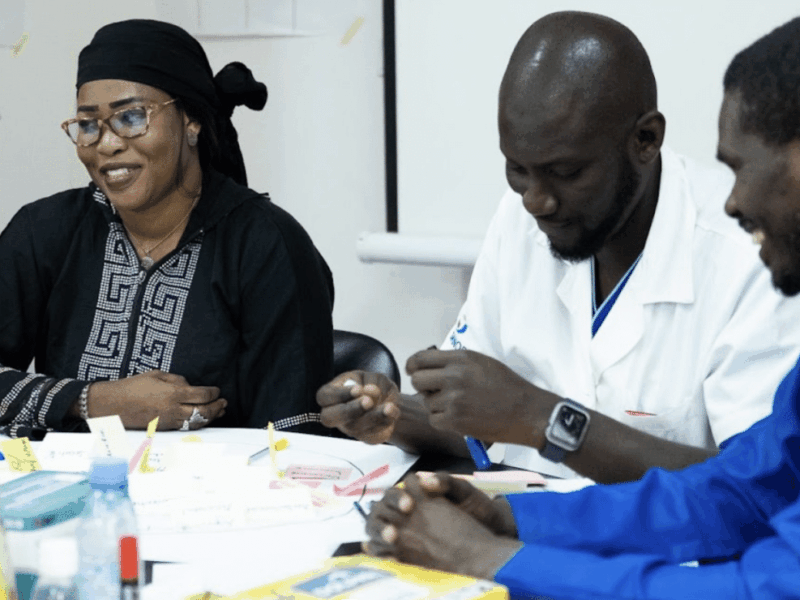

“Because of the expectations in their communities, many rural women in Ethiopia aren’t open to modern family planning until they have more than four children,” says Habtamu Tamene, director of research, monitoring and evaluation for CCP’s Communication for Health project in Ethiopia. “Bringing many children into the world is seen as an asset in these communities for many reasons, including the need to have children to work the land and for security. Our work promotes the use of modern family planning as early as possible.”

The research, led by Tamene, will be presented as a poster at the International Conference on Family Planning to be held Nov. 12 to 15 in Kigali, Rwanda. It suggests that social and behavior change programs need to help shift the social norms to encourage women to initiate the use of contraceptives early on in her childbearing years.

The Communication for Health project is using these findings to promote postpartum family planning to women. Among other efforts, the USAID-funded project created a series of videos designed to be shown in maternal waiting rooms that outline the benefits of child spacing and modern contraception. The project is using an integrated approach including radio, health facilities and a new mobile app that includes key messages about child spacing.

In August 2017, the researchers conducted 16 focus group discussions with a total of 153 men and women, in-depth interviews with 16 women between the ages of 15 and 49 with a child under the age of two as well as 24 religious leader and health workers.

“Most women start using contraceptives after finishing having all of their children,” one 30-year-old woman told researchers.

Tamene says that the push to have children starts soon after marriage, even if the brides are teenagers. “If a woman isn’t bringing a child to her husband in the first year, it a problem,” he says. “Her in-laws will not approve of her. We are trying to persuade couples to use family planning when they want and not follow the current norm.”

Some wrongly fear that using contraception before having children leads to later infertility, he says.

In rural Ethiopia, just one-third of married women between the ages of 15 and 49 use modern contraception. While the fertility rate has fallen in recent years across the country, the average number of children born per woman is 4.6 (2.3 in urban areas and 5.2 in rural areas).

Communication for Health has an uphill battle as it works to change behaviors and social norms, trying to get women to space the birth of their children by at least two years. Not only are they bucking long-standing traditions, there are also religious and other considerations.