It’s a tough job ensuring that children around the world receive their recommended immunizations.

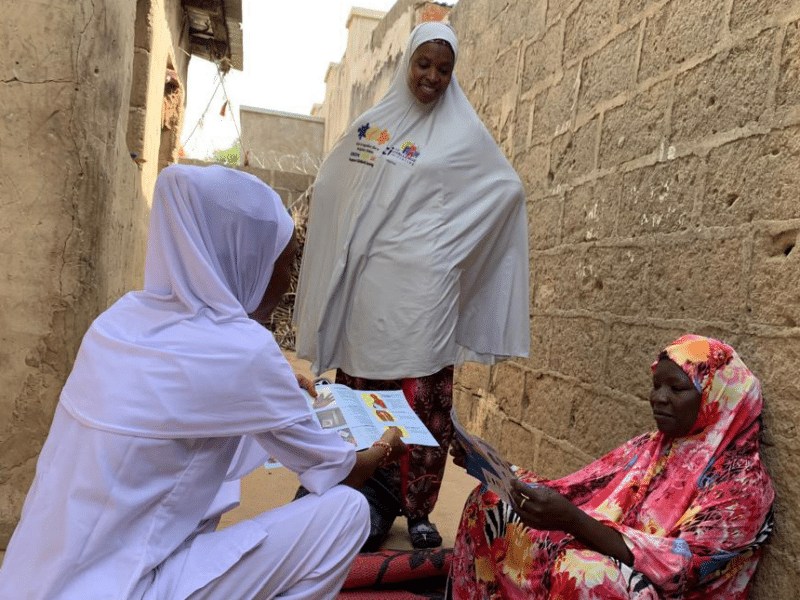

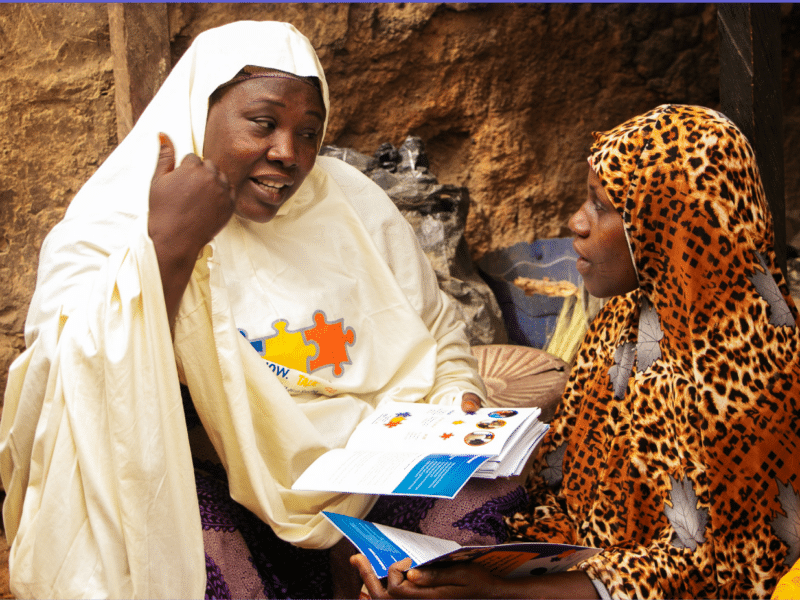

Frontline workers face a hundred small daily challenges. How do you ease the concerns of a mother who sees her baby in pain after receiving a shot? How do you counsel a reluctant caregiver to bring her child back again and again for numerous rounds of vaccines? How do you address rumors and myths – that vaccines are a plot to sterilize children or they are going to make a child sick – that may stand in the way of completing the vaccination schedule? How do you track dropouts and missing children?

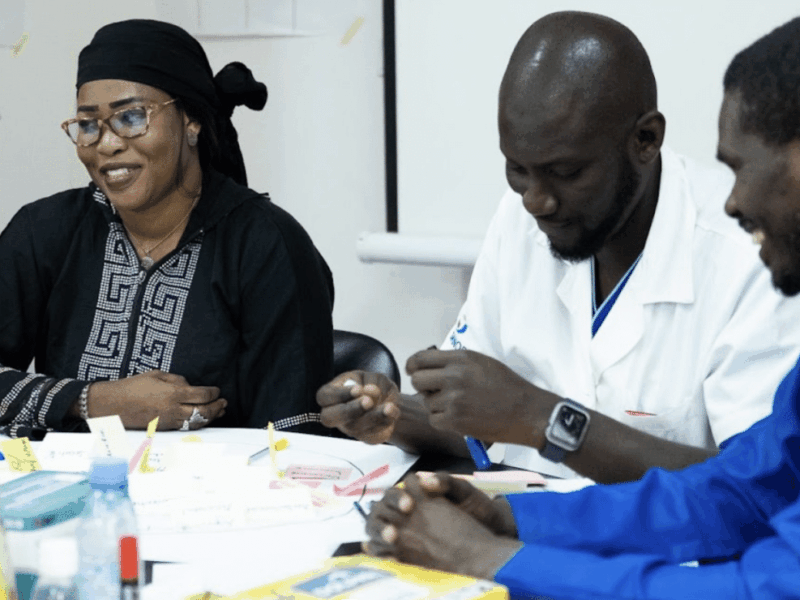

Come December, there will be a toolkit to make this difficult job a little easier. In 2017, UNICEF Headquarters and the Johns Hopkins Center for Communication Programs jointly embarked on an effort to develop a package of training materials, videos, audio job aids, reference resources and supportive supervision tools for frontline workers, be they healthcare providers, social workers, community health workers or community-based volunteers. The goal is to give frontline workers and their supervisors the interpersonal communication tools they need to build trust with caregivers and ensure children receive lifesaving vaccines.

“One critical challenge facing immunization programs is that too often caregivers aren’t treated with the courtesy and empathy necessary to motivate them to return to complete routine childhood immunizations,” says CCP’s Jvani Cabiness, who is a member of the project team. “Caregivers face a number of challenges when seeking immunization services. If they have a negative experience and their concerns aren’t addressed, there is little motivation to return for the next visit.”

Caregivers have many reasons for delaying or refusing vaccines for their children or failing to complete recommended childhood vaccination schedules. These might be individual religious, ethical, and medical considerations; the influence of anti-vaccine campaigns; fear of side effects or complications; non-recognition of the benefits of vaccination; inconvenience of services; or perceived mistreatment by frontline workers, among others.

Frontline workers are a crucial bridge between the communities they serve and immunization services. Research has shown that the quality of the interaction between frontline workers and caregivers is a key factor in ensuring completion of the routine vaccination schedule. Frontline workers are among the most influential sources of information in immunization behavior.

In 2017, according to the World Health Organization, an estimated 19.9 million infants worldwide were not reached with routine immunization services such as three doses of the diphtheria-tetanus-pertussis vaccine, putting them at risk for infectious diseases that can cause serious illness and disability or be fatal. Around 60 percent of these children live in 10 countries: Afghanistan, Angola, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Ethiopia, India, Indonesia, Iraq, Nigeria, Pakistan and South Africa, the WHO says.

“A main finding of our formative research was that frontline workers are often aware of what constitutes effective interpersonal communication, but barriers such as time constraints, workload and attitudes toward clients and caregivers can stand in the way of using it effectively,” Cabiness says. “In response, our goal is to create a global standard for not only ensuring frontline workers have the techniques and approaches to practice effective interpersonal communication but also the motivation to do so.”

A crucial element in the package is the list of frequently asked questions – and suggested answers. Simple questions include such things as what vaccine is being given, what disease is it for, what is the childhood immunization schedule. Others speak to more complex issues, such as addressing misconceptions about vaccines, side effects and more.

Countries that wish to adopt and implement the package should first conduct a needs assessment before implementing the package to make sure that interpersonal communication skills are the primary issue they face, Cabiness says. The package materials should then be adapted and contextualized based on the nature of the communication challenges in each individual country.

To ensure the global relevance of the package, CCP entered into a unique partnership with two of its sister organizations: The Centre for Communication and Social Impact (CCSI) in Nigeria and the Center for Communication Programs Pakistan (CCPP). The two groups have been part of a constant feedback loop to gather input directly from frontline workers and immunization communication experts in their respective countries.

The package is being pre-tested in Pakistan and Nigeria and CCP’s Communication for Health project will soon be testing the package in Ethiopia as well. UNICEF country offices are also conducting pretests, including a training of trainers for teams in Bosnia and Serbia. The work in those countries, Cabiness says, “demonstrates there was interest in and an immediate need for the package even before we finalized it.”

Other partners involved in the project include: Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation; Bull City Learning; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC); John Snow Inc.; Maternal and Child Health Integrated Program (USAID/MCHIP); University of Alberta and Emory University.