One in four people recently surveyed in eastern Congo told researchers that they don’t believe that Ebola is real.

This lack of understanding of the disease, the lack of trust in institutions trying and failing to put in place a control strategy, may be a key reason why the outbreak in the Democratic Republic of Congo is spreading faster, not slower, eight months after it began.

Distrust, the Harvard Medical School survey found, makes it far less likely that someone would seek treatment at an Ebola treatment center or be vaccinated against the virus. Suspicion has kept the sick from telling health workers who else they have come into contact with, making it more difficult to stop the spread of the disease. More than 1,300 residents have been sickened in the DRC and two-thirds of them have died.

What we learned in 2014 and 2015, when 11,000 west Africans ultimately died from Ebola, was that at first, yes, there will be confusion and chaos and mistrust. Civil wars in the region had decimated the health system and eroded trust in health workers. Early messages such as “Ebola Kills” created fear. Communities needed to know that while Ebola was deadly, getting early help was critical to improving the chance of survival.

A UN peacekeeper monitors the security situation while a helicopter departs from the outbreak region. Photo: World Bank/Vincent Tremeau

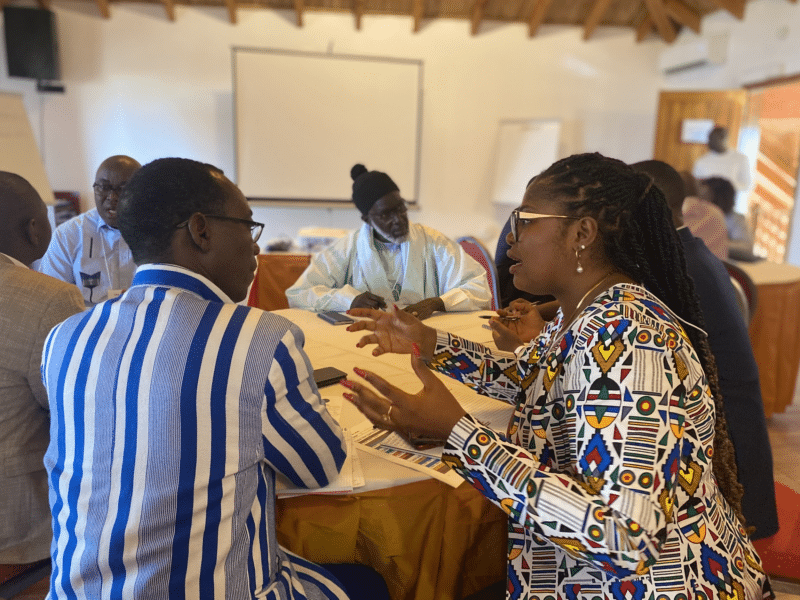

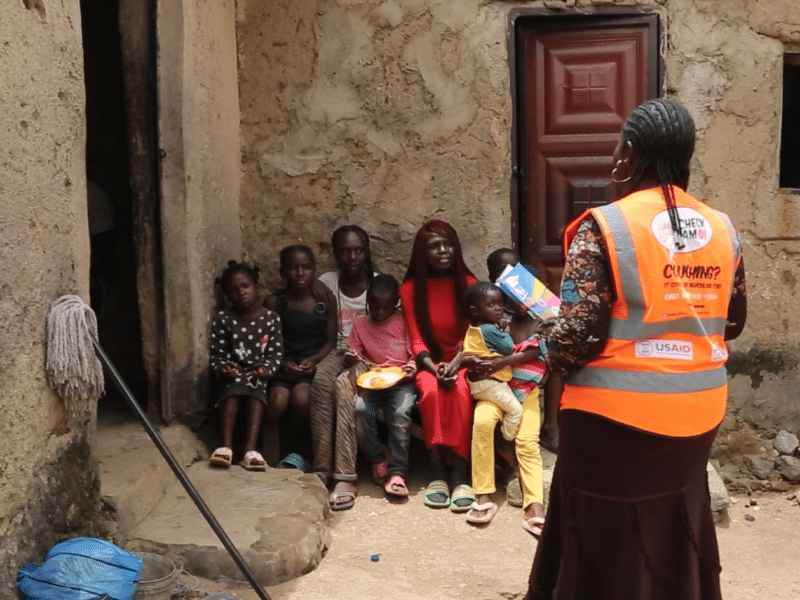

Within months, organizations who worked in the region, including Johns Hopkins Center for Communication Programs, were able to engage and gain the trust of village chiefs and community and religious leaders who, in turn, spoke to their communities about the disease, stigma, prevention and treatment. Radio spots and other social and behavior change communication materials and engagement activities were created to correct misinformation and halt its spread. It wasn’t easy – and our research shows there is still a lack of trust in the health system in many areas – but putting trusted community leaders at the center of the response and facilitating open communication and dialogue became the basis for turning things around.

While the disease is the same, the contexts are very different this time. The eastern part of the Democratic Republic of Congo has been plagued by violence for two decades. This insecurity and violence mean health workers – and accurate information – can’t move freely. Many international groups have had to pull out of the country. And there is an absolute lack of trust in the DRC government by the people. In fact, just 29 of the 961 people surveyed said they trust national authorities. That’s three percent! It’s no wonder things aren’t improving.

Our research and others’ have shown a link between distrust and reduced adherence to recommended public health interventions, that a lack of trust keeps people from seeking treatment and can stand in the way of facing down the chaos of an epidemic. This seems to be happening now, hampering efforts to contain Ebola.

Unfortunately, rather than being able to engage with communities to help spread key health messages, many international humanitarian and health organizations are stuck on the outside looking in. Aid workers have been attacked for entering into a conflict zone. One opposition leader took to the airwaves, claiming on local radio that a government lab had manufactured the Ebola virus “to exterminate the population” of one of the hardest-hit areas.

Gunmen burst into a hospital conference room on Friday and forced people onto the floor, “accusing them of perpetuating false rumors about Ebola,” according to the Associated Press. A Cameroonian epidemiologist was killed. This happened hours after attackers armed with machetes tried to burn down another Ebola treatment center.

All of this is stymying efforts to distribute a new Ebola vaccine, to trace those who have been in contact with the sick and get them help. It is also halting a flow of data that could both help hone messages designed to stop Ebola’s spread and bring improved information back to those on the ground who could best use it.

Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières, the international humanitarian organization that has been forced to leave the DRC at times because of violence over the course of the outbreak, put it this way: “The Ebola response must take a new turn: Coercion must not be used as a tactic to track and treat patients, enforce safe burials, or decontaminate homes; patients and their families must be included and empowered when it comes to decisions on how to manage the disease in their communities.”

Nine months in, we must find a way to revisit the lessons learned in west Africa, to somehow reboot and start again.

Can we identify and build on existing networks of trusted community and religious leaders in the DRC who can share credible information necessary to prevent the spread of Ebola? Can these trusted community leaders make the difference in helping their communities believe that Ebola is a real threat but that there are ways people can protect themselves? Should we be adding people with conflict mitigation or negotiation skills into the mix along with Ebola experts? Can we push back against this wave?

The authors of the Lancet Infectious Diseases study I referenced above have similar thoughts. “Engaging locally trusted leaders and service providers could help to build trust with Ebola responders who are not from these communities,” they write. “If those involved in the [Ebola] response are transparent and consistent in responding to the local needs to stop this outbreak, the trust established during this response could translate into long-term general trust in institutions.”

The Ebola outbreak in DRC provides, unfortunately, a perfect example of just how detrimental mistrust and misinformation can be to health. In many ways, it can be just as deadly as the disease itself.