To help cut through misinformation and rumors surrounding the second-largest Ebola outbreak ever in the world, the Johns Hopkins Center for Communication Programs has developed messages for a national health hotline available to anyone in the Democratic Republic of Congo who needs up-to-date – and, most importantly, accurate – information on the disease and its spread.

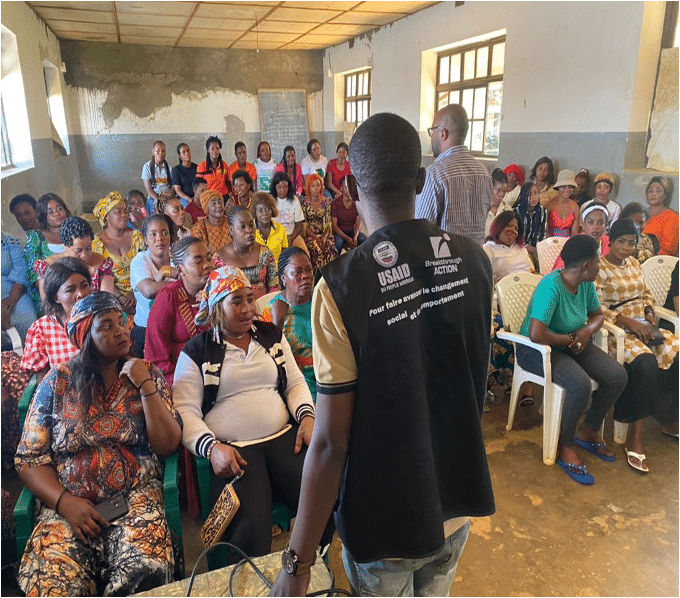

The messages, developed by CCP’s Breakthrough ACTION DRC project, reached more than 112,500 people in the first three months they were available (September through November). The project is funded by USAID.

“This use of mobile technology allows us to reach people in remote areas who lack relevant information about Ebola virus disease and provide them with localized content in a way that transcends distances and eliminates obstacles,” says CCP’s Arnold Matabaro, who works as Global Health Security Agenda advisor for Breakthrough ACTION DRC. “This new form of communication has made it possible to make useful information available for free and thus avoid the spread of rumors while strengthening people’s confidence in the official health system.”

Since August 2018, nearly 3,350 Ebola cases have been recorded in two provinces – North Kivu and Ituri – and more than 2,100 people have died. The medical and public health responses have been hindered by violence in these volatile regions, with attacks on health workers and vaccinators. Many non-governmental organizations have felt forced to leave the country because of the dangers their workers have faced.

In this type of climate, Matabaro says, it is even more important for people to be able to access information in the palm of their hands.

Residents of the DRC can call an existing health information line – 42502 – from their mobile phones to receive the new Ebola-related messages. Callers can hear about transmission, prevention and infection control, vaccination, surveillance, medical care, nutrition and dignified and secure burials. The latter can be an issue in the spread of Ebola as some African cultures have a tradition of washing their dead – a practice that can spread the dangerous virus easily to caretakers.

The messages are available in French as well as a series of local languages: Kikongo, Kinande, Lingala, Swahili and Tshiluba.