Fatima Tukur was worried. Her baby had been running a fever and now had chills. Fatima thought it might be malaria, but she wasn’t sure, so she bundled up her baby and made her way to the nearest clinic.

On the road to the clinic, Fatima grew more and more anxious. She knew malaria tests usually took all day and she had other children to care for at home. Fatima considered buying malaria medicine from a drug shop, but she wanted the reassurance of a malaria test result. She resigned herself to spending the entire day waiting in the clinic. Her baby was worth the wait.

As Fatima took a seat in the waiting area, a nurse quickly came over, checked the baby’s vital signs and administered a rapid malaria test. Fatima was surprised. Rather than waiting all day in the clinic, in just a few hours she had received the baby’s test results and medicine and was on her way back home.

Historically, clinics and hospitals have required patients to see a provider before a malaria test can be ordered and given. Once test results are ready, patients have to see the provider again to receive a diagnosis and, eventually, a prescription. But a new check-in procedure that was developed and tested by the Johns Hopkins Center for Communication Programs’ Breakthrough ACTION-Nigeria project can be credited for Fatima’s quick visit and is now poised to be a game changer for overburdened health systems dealing with malaria.

Breakthrough ACTION’s work is funded by the U.S. President’s Malaria Initiative (PMI).

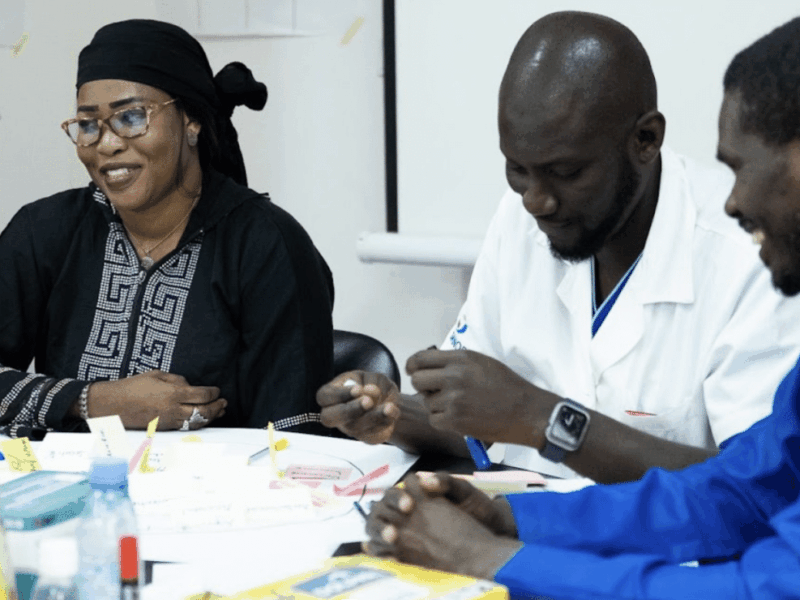

To develop this new approach to malaria testing, Breakthrough ACTION-Nigeria and the Nigeria National Malaria Elimination Programme (NMEP) used an innovative behavior change process that draws from human-centered design and behavioral economics. Using these disciplines created opportunities to work closely with health care providers across Nigeria from the beginning of the design process all the way to the solution.

In late 2019, the providers helped conduct interviews that identified “pain points” in current clinic practices. CCP, the NMEP and the health care providers then used this data to generate potential solutions, test them in clinical settings and refine them based on their findings. By working with providers to develop the new approach to testing, CCP and the NMEP increased the likelihood that it would be accepted by other health care providers.

Ultimately, the new testing approach improves providers’ adherence to malaria testing and treatment guidelines by ensuring that every patient with a fever gets a malaria test as soon as they check-in. Not only does this save patients time, but it also gives providers the information they need to make decisions about treatment right away.

Furthermore, the new procedure reduces the temptation to rely on clinical intuition, which can result in overuse of malaria medications, and reserves life-saving medicines for patients who actually have malaria.

Automatically testing for malaria before going into a consultation with a health care provider has also increased efficiency and cut down the amount of time patients spend in clinics waiting to be seen or waiting for test results and treatment.

“You see the crowd of patients waiting outside to see me? I am not worried because those who complained of fever already have their malaria test results with them,” said Mu’Awya Saidu, who runs the Primary Health Centre Birnin Yari in Kebbi State. Under the old system he would have seen them before and after the test, but now he can treat those with malaria in just one visit. “This has made my work easier,” he says.

The three states in Nigeria that participated in developing the testing approach now have a new tool in their fight against malaria. More importantly, it is a tool that can be put into use in other states at no additional cost. Providers hope it will, ultimately, lead to better use of life-saving malaria drugs and quality of care for patients with fever, like Fatima’s baby.

A version of this story first appeared on PMI’s website.