Anamika Kumari Mishra’s father got sick and died almost a decade ago, leaving the now 16-year-old with a single mother. Anamika’s mother had considered marrying off her daughter, as she couldn’t afford school fees and she wasn’t sure what kind of future Anamika would face.

Anamika’s story is pretty typical in the Durga Bhagawati municipality where she lives in rural southern Nepal. But the municipality wants to change the narrative.

It recognizes the social pressure that parents are under to arrange early marriages for their daughters, despite the legal age of marriage in Nepal being 20. Seventy percent of girls, a local census revealed in 2022, are marrying early. A 2019 study found that 38.4 percent of women in Nepal between the ages of 20-49 reported they had been married before the age of 18.

To tease out some of the reasons why child, early and forced marriages are so common in Nepal – and to develop ways to halt the practice – the municipality has been working with the Johns Hopkins Center for Communication Programs-led Breakthrough ACTION project. Through a recent human-centered design process, Breakthrough ACTION, funded by USAID, has helped municipalities find ways to change existing early marriage social norms. These solutions aim to instill pride and prestige in the community for supporting girls to marry only after they are 20 years old.

Why wait to get married? Evidence has shown that girls under 18 are not ready to become wives and mothers and are more susceptible to domestic violence. Child marriages increase the risk of early pregnancy which can lead to complications during pregnancy and childbirth, and maternal mortality. Girls who marry early often miss out on opportunities necessary to become independent and economically productive adults.

This week, UNICEF marks what it calls the “International Day of the Girl Child,” which focusses on the unprecedented challenges girls face to their education, their physical and mental wellness, and the protections needed for a life without violence. Stories like Anamika’s shed light on the needs of girls around the world.

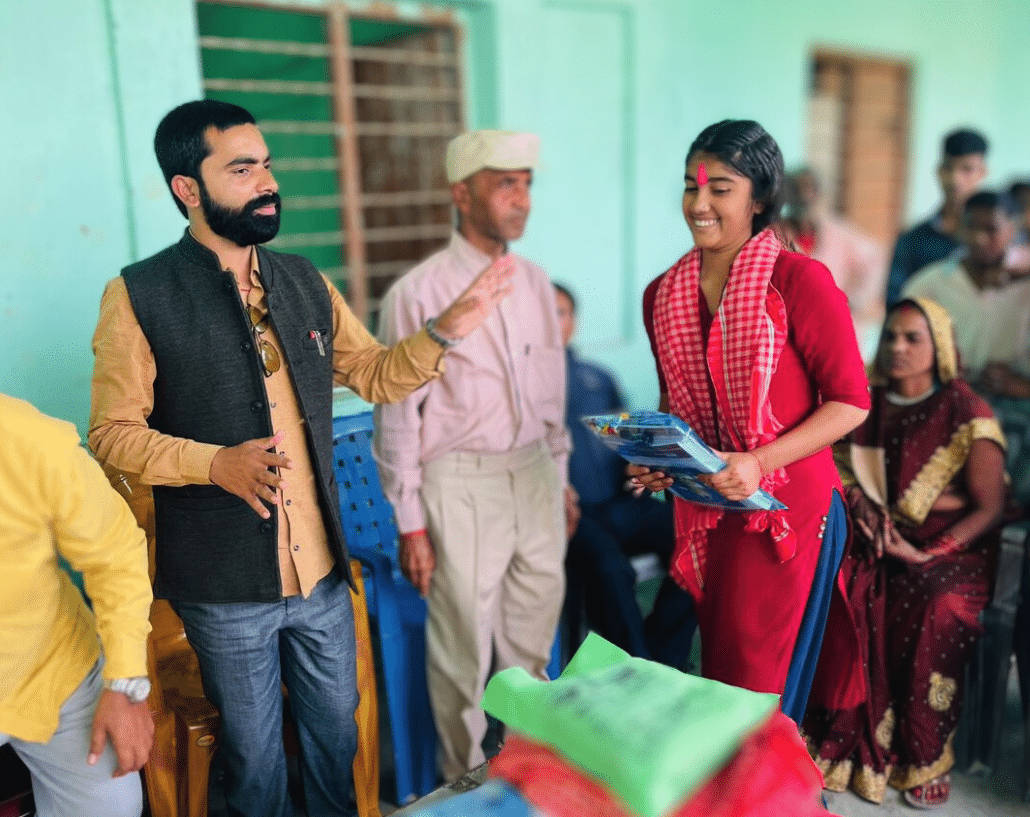

One of the potential local solutions developed in the HCD process was designed to award scholarships to girls, paid for through a municipality’s budget, to show appreciation for girls and support them so that they can avoid early marriage. Now, there are scholarships for all children in the public schools during 11th and 12th grades in two project municipalities. More than 459 students now can continue their studies. The municipalities aims to continue the program for years to come.

And Anamika? She is not only getting her school fees paid, but since she scored the highest on the 10th grade exams, she is receiving an additional scholarship worth US$120 (15,000 in Nepali rupees) for her further education

For Anamika, who now lives with her maternal uncle, the scholarship is allowing her to move forward, rekindling her dreams for the future. She had lost hope due to her financial situation, but this initiative boosted her spirits.

“When neighboring women used to suggest to my mother to arrange my marriage, I wasn’t sure I could continue my education since my mother alone couldn’t afford it,” she says. “But now, my hope has returned after receiving the scholarship to continue my higher education.”

Says CCP’s Pranab Rajbhandari, country manager in Nepal:“The majority of parents in Madhesh province desire to support their daughters to marry later to help their daughters’ aspiration for higher education, employment and independence. But due to social and economic pressures, they alone are unable to do so.

“This enabling support provided by the local government is highly encouraging as it helps to set an example, provides alternatives for the girls and their parents to help change the narrative that girls must be married off early.”