Antimicrobial resistance, which occurs when micro-organisms evolve and are no longer responsive to standard treatment, is driven by human behavior and policies, especially the misuse and overuse of antimicrobials in the medical, veterinary and agricultural sectors.

When this happens, previously treatable infections can spread rapidly and further increase the risk of severe illness and death, increasing health care costs and ultimately undermining a community’s ability to deal with known and unknown health threats.

That’s why social and behavior change activities – from increasing awareness and knowledge of antimicrobial resistance to helping human and veterinary health providers understand how they can avoid contributing to resistance – might be the way to slow down the excess use of antibiotics, antivirals, antiparasitics and antifungals in order preserve the effectiveness of these life-saving medications long into the future.

A recent “Trending Topic” on the COMPASS website, written by the Johns Hopkins Center for Communication Programs, argues just that.

“One of the drivers of antimicrobial resistance is a lack of awareness or understanding of how it arises and the magnitude of the problem it poses,” says Issiaga Daffé, who leads CCP’s work in Senegal and Mali. “How do we raise livestock and care for them when they are sick? How do we prescribe, take, and dispose of medicines in our homes and in our health care facilities? So many factors contribute to the problem.

“This presents an opportunity to utilize social and behavior change approaches to effectively tackle the global issue.”

The World Health Organization has declared antimicrobial resistance “one of the top ten global public health threats facing humanity” and this week is World Antimicrobial Resistance Week.

“Antibiotics are becoming increasingly ineffective as drug-resistance spreads globally leading to more difficult to treat infections and death,” according to the WHO. “New antibacterials are urgently needed … However, if people do not change the way antibiotics are used now … [any] new antibiotics will suffer the same fate as the current ones and become ineffective.”

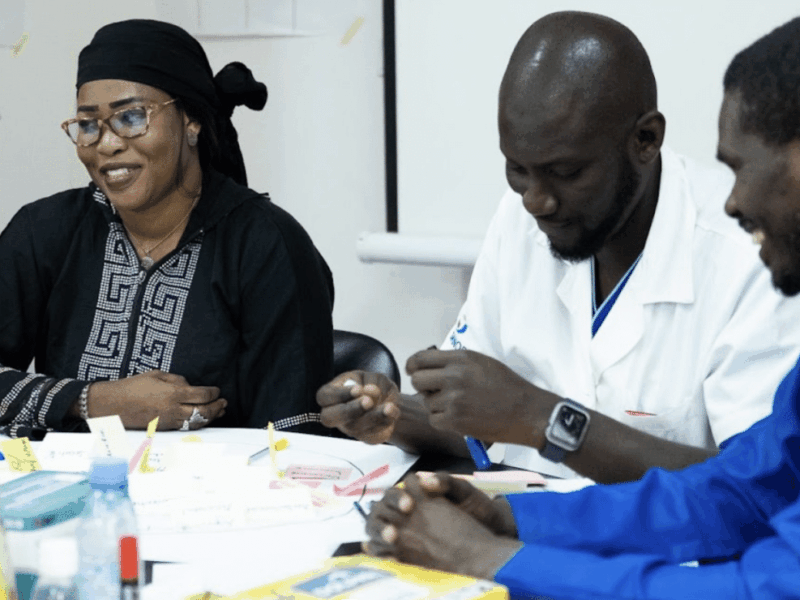

CCP has in recent years begun working in various countries to help reduce the threat of antimicrobial resistance including Cote d’Ivoire, Senegal and Nigeria, where the work primarily targets healthcare workers to make sure antibiotics and other medications are only given when necessary. In some cases, patients or parents press hard for these treatments even when they aren’t called for, increasing overuse.

A report commissioned a decade ago by the British prime minister estimated that unless action is taken, as many as 10 million people could die from antimicrobial resistance each year by 2050.

Not only does CCP work with healthcare providers to lessen the risk to humans, but program officers also work with veterinarians and the agriculture sector to create messages designed to prevent the same overuse issues in animals and on farms. Messages about antimicrobial resistance in animals will be better received if they come from veterinarians as opposed to health workers who care for humans.

“These questions are so interconnected, and we need to change behaviors on all of those fronts,” says CCP’s Obinna Onuoha, senior program officer for risk communication and community engagement for the CCP-led Breakthrough ACTION-Nigeria project.

He calls antimicrobial resistance an “invisible process,” as it happens out slowly and largely unseen.

“One of the complexities of communicating about antimicrobial resistance is that you need to increase people’s understanding of what it means,” he says. “Every audience needs a bit of a different message depending on where they fall in those practices and what the main dynamics are in each sector.”

Several community or consumer factors also drive antimicrobial resistance. Examples are indiscriminate use of antibiotics without prescription, low uptake of vaccinations, and poor hygiene practices. Social and behavior change helps with understanding what drives these practices and works to address them through implementation of appropriate interventions.

Onuoha says that there needs to be continuous conversations with human and veterinary health providers to become better stewards in the dispensing of antimicrobials, while educating individuals and communities not to self-medicate and only take prescriptions from qualified doctors.

“One way we are trying to do this is by engaging school-aged children with key messages on antimicrobial resistance,” he says. “That way, we are catching them young and helping them develop healthy behaviors for the future. We want to help everyone understand how they can play a role in avoiding antimicrobial resistance.”

A study conducted in Senegal as part of Breakthrough ACTION suggests that the specific needs of each sector, from human to environmental health through the development of adapted communication materials, must be considered.

“If you knew how fungicides are used in our fields, you would understand the level of risk to human, plant and animal health, and the threat to food safety,” said one participant at a workshop to develop communication materials.

In Sierra Leone, since the establishment in 2017 of a working group on antimicrobial resistance, “little had been done in terms of community awareness and social behavior change interventions,” says CCP’s John Idrissa Koroma, a senior program officer there.

Things have gotten worse, says Fasalie Sulaiman Kamara, another senior program officer with Breakthrough ACTION in Sierra Leone, because of a proliferation of untrained peddlers who are selling antimicrobials and spreading misinformation about them, without a thought to the consequences on a broader scale.

Now, though, Koroma says, “a more robust and coordinated effort should be in play, as social behavior change is as critical to help people been informed on the dangers of drug abuse and antimicrobial resistance.”

CCP’s Mouhamadou lamine Balde, Breakthrough ACTION’s chief of party in Senegal, says it will be easier to combat some difficult behaviors without overwhelming people with too much technical information. That’s why messages provided in simple text and in a way that is relatable in everyday life could be a good start.

“It’s the small doable actions that can help,” he says.