Research shows that health emergencies often exacerbate existing gender inequalities around the world. Women, especially in rural areas, frequently bear the brunt of these crises due to their caregiving roles and limited access to health information. They become more vulnerable if they are overlooked in emergency response strategies when gender-sensitive approaches are not used.

To this end, the Johns Hopkins Center for Communication Programs-led Breakthrough ACTION project in Guinea piloted a curriculum designed to promote equitable responses to health emergencies and to look at what gender integration within risk communication and community engagement (RCCE) interventions looks like.

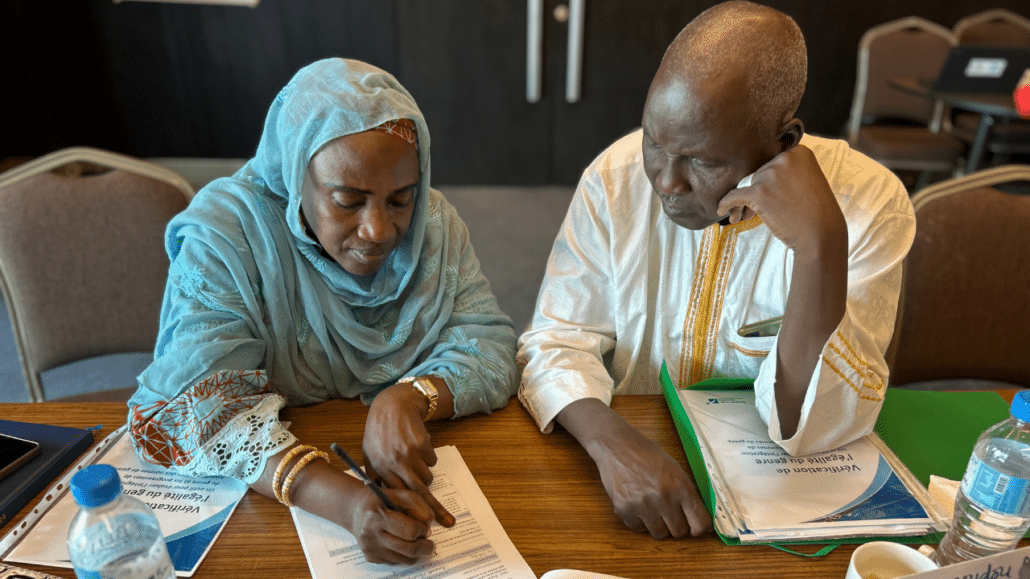

The five-day workshop they created dug deeply into what gender means in terms of roles, stereotypes, power dynamics – and their impact on health – and the diverse needs of different groups in society. These elements are crucial to understanding the risk and discriminatory factors that put women in vulnerable situations.

The new curriculum is unique in that, “it’s one of the first in-depth trainings on integrating gender into risk communication and community engagement and zoonotic diseases for activity implementers.” says CCP’s Antonia Morzenti, a senior program officer who helped develop the curriculum.

“In the past, reaching ‘gender parity’ meant successful gender integration, making sure women were in the room participating in a community activity,” she says. “Now participants understand that integrating gender is a multitude of strategies and approaches that can and should be intentionally applied throughout the program lifecycle to take gender considerations into account and compensate for gender-based inequalities that they are now more aware of. It’s more than a seat at the table.”

Participants analyzed in-depth how to account for gender more fully in their projects, examine gender disparities, adapt programs to meet the specific needs of those from different socio-demographic backgrounds, intentionally involve men and boys in RCCE activities, and aim for a sustainable transformation of social norms leading to a healthier, more gender-equitable society.

The success of the Guinea training inspired its expansion to Niger, where it was tailored to fit the local context while maintaining its core objective: to foster a transformative shift in how project implementers consider gender in RCCE and health emergency responses.

In December, Esete Getachew, CCP’s gender, equity, and social inclusion deputy lead, will take the training to Cameroon to further share approaches to ensuring that gender inequalities in the analysis, planning, design and implementation of policies are considered, along with actions to address the different situations and needs that may arise.

In health projects, Morzenti says, stakeholders and project implementers have often misunderstood the concept of gender and its role in health projects, frequently associating the term “gender” solely with women or men. This lack of understanding, accentuated by social and cultural norms, has been a major obstacle to the effective learning and implementation of health interventions. Moreover, even at a global level, the concepts of gender equality and gender integration are relatively new and available guidance and technical information contain gaps.

To reduce health inequalities between women and men, health programs must consider an intersectional gender perspective, which looks at all risk factors and discriminatory factors that put women and other marginalized groups in a vulnerable situation, she says.

Sekou Omar Magassouba, who works at the National Health Security Agency in Guinea, was one of the attendees of the pilot training. He says he plans to apply the concepts he learned by accounting for gender when organizing capacity building initiatives for key players, adapting training module content to include this dimension, and considering the specific needs of men, boys, women and girls when designing awareness raising messages.

The effectiveness of the Niger training was clear in the results of the pre- and post-tests, which revealed a significant increase in participants’ knowledge. Specifically, results demonstrated an improved understanding of key concepts such as “gender,” “gender norms,” “unconscious bias,” and the different phases of a project cycle.

Recent research published in the Archives of Public Health notes that when facing the same health problem, hospitalization rates are generally lower in women than in men, which suggest not that women don’t get as sick but that women could face more obstacles in accessing health care. “Analysis of health crises must take into account an intersectional gender perspective to ensure equitable health care,” the authors write.

Participants left the training in Niger not only with new knowledge but also with a conviction that integrating gender into health programs can help create lasting change.

“Before this training, I overlooked the integration of gender into projects and programs, and my perception of gender was limited to the concept of biological basis,” says Adamou Balkissa Elhadj Saidou, a hygiene inspector with Niger’s Ministry of Public Health, Population and Social Affairs.

Ali Safia Alfou, Community Health Department Manager within the ministry, said she sees a future of thinking about gender in new ways to solve her nation’s most pressing health problems. “Gender integration in our projects and programs contributes effectively to the success of our interventions in the long term and will have more sustainable outcomes,” she says.