The team of researchers, it seems, talked to nearly everyone who knows anything about tuberculosis. For three weeks in August, more than 30 of them fanned out in four Nigerian states to try to figure out the reasons why Nigeria has one of the highest rates of TB in the world.

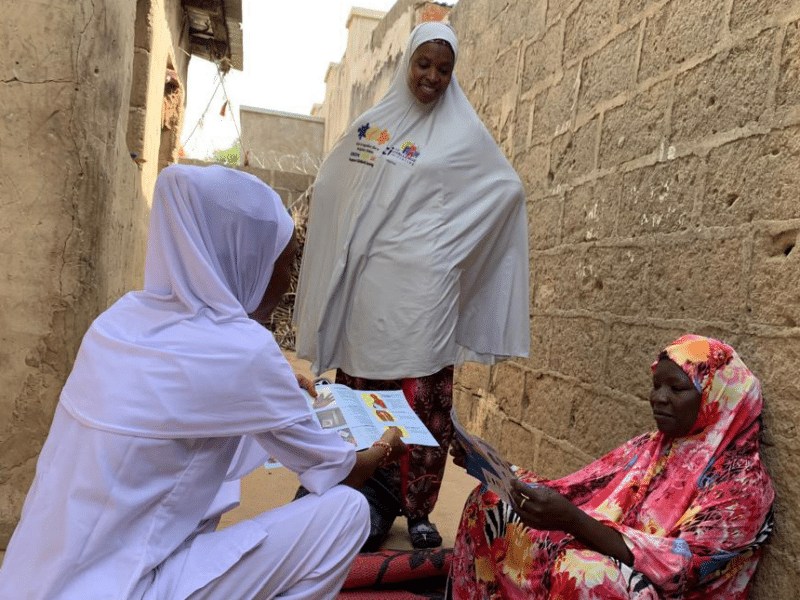

They spoke to more than 240 people – TB patients, treatment supporters, health providers, community leaders, state officials, pharmacists, traditional healers and more – to fully understand the scope of the problem from the perspective of those who know it best.

In Nigeria, it is estimated that just one in four TB cases are diagnosed and reported to the National TB Leprosy and Control Programme.

“We have our assumptions on why the TB case detection rate is so low,” says Bolatito Aiyenigba, deputy project director for malaria and tuberculosis on CCP’s USAID-funded Breakthrough ACTION project in Nigeria. “But this process is helping us to question those assumptions and to look at the problem in a new way.”

The research team, led by Breakthrough ACTION, was made up of people from Nigeria’s National and State TB and Leprosy Control Programme and partners implementing TB activities, including TB Network, Challenge TB (KNCV) and the Association for Reproductive and Family Health (ARFH). With the ultimate aim of increasing Nigeria’s TB case detection rate, the research team set out to put themselves in the shoes of their end users.

“We are immersing ourselves in our target audiences’ lives, observing their environment, and having conversations with them about their TB journeys,” says CCP’s Jennifer Orkis, who is leading the process in Nigeria. “We are learning how the health facilities interact with patients, how patients interact with their treatment supporters, how TB service providers interact with lab technicians – how the entire ecosystem around TB operates.”

This type of deep dive is becoming the norm for Breakthrough ACTION in order to get the truest sense of what is needed to solve some of the world’s most pressing health challenges. The project already led a similar effort in Zambia across a number of health areas, with plans to also ramp up efforts in Cote d’Ivoire, Jamaica and Guyana.

In some areas, Nigeria’s research team has been able to reaffirm what’s been long suspected. In others, they are gleaning new insights.

“Stigma, discrimination and an overall lack of awareness of TB are proving to be major barriers to going to the facility for a TB test,” Aiyenigba says. “We now have deeper insights into the ‘why’ behind this through patients’ stories.”

“We’re finding patients spend a lot of time seeking care, but do not go to the right places,” adds Joseph Edor, a senior staffer for Breakthrough ACTION Nigeria’s TB program. “They often start at the local pharmacy, or by visiting a traditional healer, or by using home remedies. This results in delayed diagnosis and improper treatment.”

Myths and misconceptions around TB are plentiful. People believe, for instance, that TB is caused by smoking, drinking and witchcraft, that it is hereditary, and that it can be cured with burnt crab, ashes and oil. While TB testing and treatment are free in public health facilities, many people don’t know this, don’t believe it’s true, or still incur costs, which impact initial health-seeking behavior and adherence to treatment.

The process has also enabled the team to take a closer look at structural issues impacting case detection.

“We’ve found that a number of presumptive TB cases do indeed make it to the health facility – but incomplete or incorrect data entry results in missed opportunities for diagnosis,” Orkis says. “We’re also seeing instances where health workers are collecting large numbers of sputum samples, but labs are unable to test the number of samples they receive.” Broken machines and challenges transporting and refrigerating samples are contributing factors.

TB is a contagious infection that usually attacks the lungs and is spread by coming into prolonged close contact with someone who is infectious. Today, most cases are cured using the internationally recommended strategy for TB control, known as DOTS (Directly Observed Treatment, Short Course), a strategy that Nigeria follows. A combination of health facility staff, family members and community volunteers are supposed to watch a patient taking their medication every day. However, the research team learned that DOTS is not always directly observed.

“While all patients are meant to have treatment supporters who directly observe the patient taking their drugs, not all treatment supporters fit the recommended criteria or understand their role,” Aiyenigba says.

The rapid, visible progress patients make when placed on treatment seems to be both a help and a hindrance. While it can uplift and motivate both patients and providers alike, it also seems to contribute to people discontinuing treatment when they start looking and feeling better, even though they must finish the treatment to be fully cured. This indicates there may be a need to develop new interventions at critical points in a patient’s treatment journey.

In a field that traditionally takes a more clinical approach, the social and behavior change (SBC) lens has opened new doors for those working in the space. “In 15 years, the program has never thought about how to change people’s behavior,” said one member of the team.

The next phase, scheduled to begin at the end of October, will involve imagining a wide range of ways in which the team might address all that was gleaned in August. Ideas will be narrowed down and focused, and prototypes created, tested and refined together with the target audience.

“There are an incredible number of opportunities for us to help drive up the number of TB cases detected in Nigeria,” Orkis says. “And the more we understand the nuances at play here – and meaningfully involve the people we’re designing for throughout the process – the better our chances of designing something that will work.”