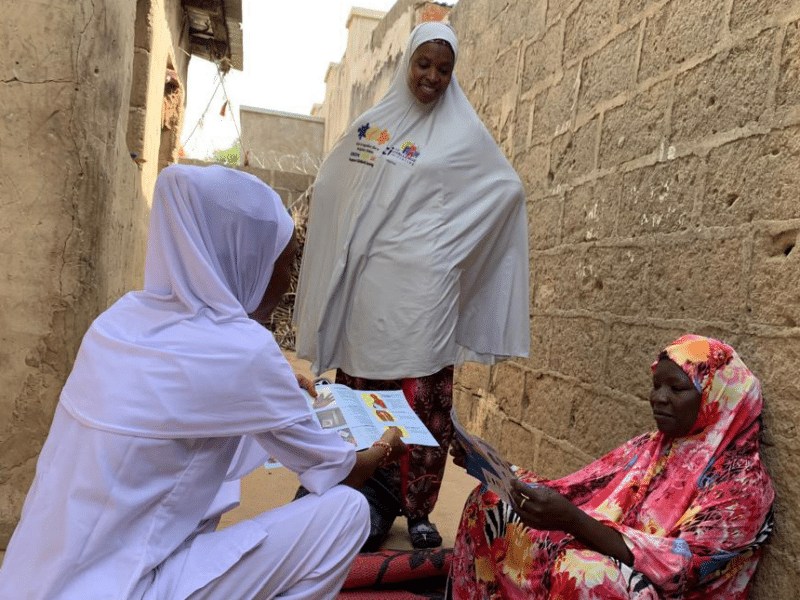

“Do you know?” the T-shirts ask, “You can get pregnant soon after delivery.”

Those who wear the shirts are part of the Post-Pregnancy Family Planning project, led by the Johns Hopkins Center for Communication Programs and funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation and Merck for Mothers. The project’s goal: To help women understand how soon after birth they can become pregnant – and what their modern family planning options are.

The focus is on women who get prenatal care and deliver their babies in private health facilities. In Lagos, Nigeria’s largest city with over 23 million residents, most women give birth in one of the thousands of private health facilities that thrive in the city. But few of those facilities were offering family planning services. Many women with infants were at risk of getting pregnant with the next child before they were ready.

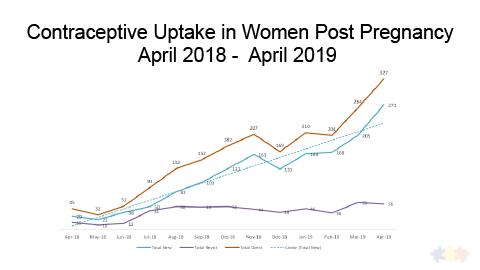

Through a combination of strategies, the project has boosted the number of women who adopt modern contraception after giving birth by more than seven-fold from April 2018 to April 2019 in 40 private facilities in Lagos targeted in a pilot project. The strategies are now being scaled up to an additional 200 private clinics over the next year.

“Even though women were sitting in the clinics waiting for maternal health services, the private clinics were not providing family planning information or promotion and the clinic didn’t even stock critical contraception supplies,” says CCP’s Taiwo Johnson, MD, the project’s technical lead in Lagos. “Now, women in these facilities are learning about post-pregnancy contraception from their first prenatal visit until delivery and beyond and are able to get contraception at that clinic.”

Working with private facilities has been a challenge. Since the facilities are run independently, Johnson and her colleagues must get buy-in from 40 individual medical directors who run their clinics in 40 different ways.

Now, the clinics are well-stocked, staff is better trained in family planning and the clinics promote these services. Informational materials are available for women in waiting rooms and the CCP-developed Serigbo TV series and music videos – with their family planning messages – play on monitors. Women who have adopted a family planning method after pregnancy are invited to talk about their experiences with those in the waiting rooms.

Often, women think that they can’t get pregnant in the first year while breastfeeding, so counselors need to be able to counter misconceptions. Every time pregnant women visit the clinic, counselors explain why post-pregnancy family planning is so crucial to their well-being and that of her child. Health workers even go to new mothers’ rooms soon after delivery to pitch the idea again.

Uptake was slow in some facilities, but then came the scorecards.

Each of the 40 participating clinics earned a rating of how well they are doing to improve the quality of services and tracking how many women are adopting contraception in the year after giving birth. Those doing well earned green ratings; those doing poorly, red. And every scorecard very clearly highlighted how each and every facility – by name – was performing.

“I scored seventh out of 40,” one clinic director complained to Johnson. “That’s failing.”

These eye-opening realizations convinced many clinic directors to reduce the cost of family planning, do a better job documenting their family planning statistics and be better advocates for post-pregnancy family planning. The positive trajectory has been even more pronounced since February when the scorecards came out.

“We have been very successful at generating demand for family planning services among women who are already clients at these private facilities,” Johnson says. “And a little friendly competition hasn’t hurt either.”