“One of the first COVID-19 rumors I dealt with – about washing yourself everyday with hot water – ironically came from my father,” says Aicha Goin, who runs Côte d’Ivoire’s “143” helpline for the Ministry of Health and Public Hygiene. She is sitting in the bustling call center, talking over the low buzz of operators working around her.

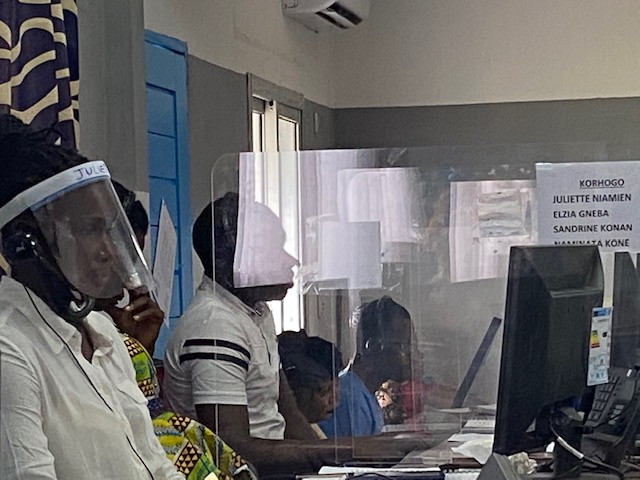

“Remember this place a few weeks ago?” she asks. All around her telephone operators are answering back-to-back-to-back calls. A team that was once 22 is now up to 64 operators, swelling in a matter of weeks to answer questions 24 hours a day. Most of the questions are from people anxious and frustrated about COVID-19. Since the pandemic began here, the Ministry of Health and Public Hygiene has also upgraded the call center’s internet and improved telephone operator stations.

One of the reasons the call center was able to pivot so quickly to COVID-19 is because of the work already being done by the Johns Hopkins Center for Communication Programs and its USAID-funded Breakthrough ACTION project. Since 2015, CCP has worked with the 143 hotline to get quality health information to Ivorians. Most recently, CCP has worked with government groups to implement a dynamic community listening and rumor management system for crises related to five priority zoonotic disease groups in Côte d’Ivoire including Ebola, dengue, rabies and more.

The rumor tracking system was designed to effectively collect and use misinformation from the public to strengthen communication in the event of a public health crisis. It’s a collaboration with the 143 hotline and the risk communication technical working group of the National Institute for Public Hygiene.

CCP is also developing other rumor tracking programs in South Africa and Eswatini related to the current pandemic, which has sickened more than eight million people around the world and killed nearly 440,000. Some projects work with national hotlines to collect rumors into a central database, while others draw from mobile surveys, social media or community-based key informants. CCP has also developed guidance on how others can set up their own rumor monitoring programs.

CCP’s expertise in social and behavior change communication lends itself to grouping rumors into standard attitude and belief statements that can be tracked over time.

The Côte d’Ivoire pilot program was launched in late 2019. Initially, in February, only a handful of people were trained. There was no public health crisis happening, after all.

“This training allowed us to better understand how the system works to take into account the rapid changes in public awareness and attitudes, as well as the prejudicial beliefs and misinformation that occur during a crisis,” Aicha says.

Following the training, the dynamic listening system was immediately set in motion, with the 143 call center receiving rumors via a WhatsApp number and direct calls to the helpline. When the pilot launched, the country was battling an outbreak of dengue so many of the rumors were related to that. All rumors were entered into a DHIS 2 platform by the call center operators.

The DHIS2 platform allows the helpline staff, with support from CCP researchers, to code and classify rumors and visualize them on a real-time dashboard. While not population-representative data, the rumors provide a window into misinformation that may be circulating in communities, facilitating a rapid response.

Just two weeks into the pilot program – on March 11 – Cote d’Ivoire announced the first case of COVID-19 in country. Suddenly, all of the plans that Breakthrough ACTION and the government had made needed to be scaled up rapidly. There was an urgent need for the critical role of the 143 helpline in the national response and the program quickly expanded.

“The helpline was stormed by the population,” Aicha says.

Having the rumor management system already in place made it possible to effectively identify rumors about the novel coronavirus and analyze and prioritize rumors in report briefs every two days. The reports allowed the government’s communications working group to rapidly make recommendations and provide the right information to the population.

Many different types of COVID-19-related rumors have circulated in communities, from the very imaginative to the most banal, from the dangerous to the mostly harmless, especially via social media. People call to confirm rumors that COVID-19 can be prevented by bathing before 5 a.m. or drinking very hot fish soup, Aicha says. Others have said that “koutoukou” (a local alcoholic aphrodisiac drink) kills the virus.

To address these rumors, the team created flyers about COVID-19 transmission and the importance of masks (and coughing into your elbow) to prevent of COVID-19, which were then disseminated by mayors, community leaders and such public places as banks and supermarkets.

Aicha says she is grateful to have had this new rumor tracking system in place at a time when Cote d’Ivoire needed it most.

Still, there is a long road ahead “This does not mean that there are not still challenges, including the regular and daily capture of rumors,” Aicha says. “[But we are] fortunate that these issues are addressed with the technical and financial support of USAID’s Breakthrough ACTION project.

“Having the rumor management system already in place made it possible to [effectively] identify rumors and to make recommendations and provide the right information to the population.”