The Johns Hopkins Center for Communication Programs’ work in Cote d’Ivoire to encourage at-risk men to be tested for HIV and, if diagnosed with the virus, initiate antiretroviral therapy (ART) was highly successful, according to an evaluation of the Brothers for Life program there.

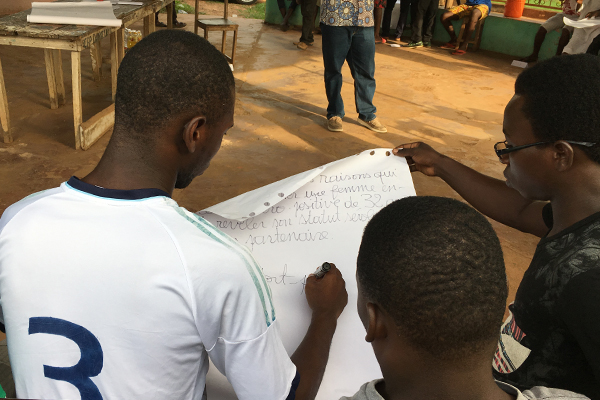

Brothers for Life is a series of small facilitated and interactive sessions that allow men to talk about topics including sexual and reproductive health, their roles as sex partners, their roles in families and society, and HIV. It is designed to help prevent men from getting HIV and, if they test positive, to start treatment.

“Many countries struggle to engage high-risk men in HIV services,” says Diarra Kamara, who leads HIV programming for CCP in Cote d’Ivoire. “What we were able to demonstrate is that Brothers for Life plays an instrumental role in ensuring that at-risk men are tested for HIV – and helps them make behavior changes that could prevent future HIV infection.”

The program evaluation included program data and surveys as well as in-depth interviews with participants. After creating a better tool for determining who is at risk for HIV infection, 3.6 percent of those involved in the Brothers for Life program tested positive as compared to the HIV prevalence rate of 1.9 percent in Cote d’Ivoire. Of the men who tested positive, only three percent did not initiate treatment within six months of testing. Ninety-three percent of the men who initiated treatment did so within four days after testing positive. Of those who began treatment, 100 percent were still in treatment six months later.

One of the biggest barriers to testing, Kamara says, is the fear of what a positive result can mean. Many fear social isolation and a blow to their masculine identity if found positive. With Brothers for Life, there is a camaraderie built, a safe place where the men can talk about their fears and how to overcome them. Those who test positive, meanwhile, are linked with peer navigators who support them in initiating and staying on treatment.

“We told ourselves what? Once you have HIV, it is finished for you,” one man, who tested positive for HIV, told researchers. “But with the Brothers for Life program … it showed us that you can have HIV and go about your activities if you follow your treatment.”

Another man told researchers that he had taken to heart the Brothers for Life conversations about how he could be putting his family at risk by having multiple sexual partners. “I stopped all that,” he says. “I stayed sincere with my wife in my home. I know that it made me change.”

In Cote d’Ivoire, Brothers for Life began under the five-year, USAID-funded Health Communication Capacity Collaborative (HC3) and continues under the five-year USAID-funded Breakthrough ACTION project. The findings from the evaluation have been used to further improve the implementation of a new testing component under Breakthrough ACTION.

The success of Brothers for Life, Kamara says, “has potential for replication elsewhere in Cote D’Ivoire and other countries in Africa.”

English and French versions of the report are available online.