So much effort in international family planning is focused on getting adolescents and women to start using modern contraception for the first time.

But what about women who have tried one form of birth control or another and quit because they didn’t like the side effects? One Demographic and Health Survey study found that women who have used contraception in the past make up 38 percent of the unmet need for modern contraception across 34 countries. That means many who have discontinued their contraception (either due to misinformation or uncomfortable side-effects of a particular method) may want to try again but may not be sure how to do so.

“These women should be easy to reach,” says Uttara Bharath Kumar, a social and behavior change expert at the Johns Hopkins Center for Communication Programs. “It’s not like you have to help them to decide to use family planning methods. That’s the biggest hurdle. And these women want to use it. So, we worked to get to the bottom of what some of the main reasons why women stop using contraception are and how we could best address them.”

In the Philippines, as in many countries, there is scarce data around what is driving contraception discontinuation. Little was known about what drives women to stop using contraceptives even if they do not plan to get pregnant, and what barriers may be preventing them from finding a method that works for them.

There’s a need to normalize the fact that it is okay to switch. Many women need to try more than one contraceptive method before finding the one that works best for them.

“Just think if someone simply said to you, when you got your contraceptive method, ‘hey, you know, every method isn’t for everybody. If there’s something uncomfortable about this for you come back, and we’ll find another one that works,’” Bharath Kumar says. “Literally, that’s all you want to hear. And then you don’t feel like a failure. Because sometimes you get a method that you think works for everybody, so should work for you too. And it doesn’t work for you. And you feel like ‘Oh, I don’t want to go back and face the provider. She may think I am complaining.’”

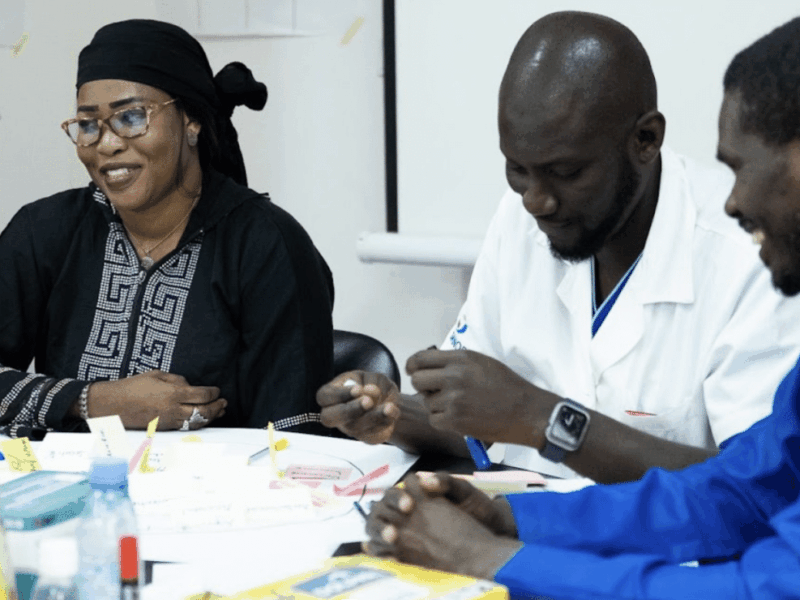

Using a human-centered design approach, the CCP-led Breakthrough ACTION project and the USAID-funded ReachHealth project – alongside the Philippine government – worked with women, health providers and other stakeholders to understand why women discontinue their contraception use (aside from the most obvious reasons such as wanting to get pregnant).

They heard from women who had anxiety about side effects they were experiencing, trusted misinformation from peers about certain methods, did not feel they could easily discuss contraceptive use with their partners, lamented that they didn’t understand all their options, and did not feel comfortable enough with service providers to go back and discuss alternative contraceptive options.

For their part, providers sought to help clients but lacked established relationships, so clients did not feel confident in approaching them for advice.

“We’ve always heard anecdotes as to why women ‘drop out,’” says CCP’s Billie Puyat Murga, a senior program officer working on the USAID ReachHealth project in the Philippines. “But this process allowed us to systematically collect and document the stories of these women, their partners and providers. Now we can now actively work to address them.”

The product of that work is the Contraception Discontinuation Toolkit, which guides social and behavior change and family planning practitioners on testing six solutions that address contraception discontinuation in their local context. Tested once in the Philippines, these prototypes are meant to be tested again in other countries and adapted to the needs of providers and women in each context. The toolkit provides step-by-step instructions for testing the prototypes, along with details on who should test them, and testing requirements.

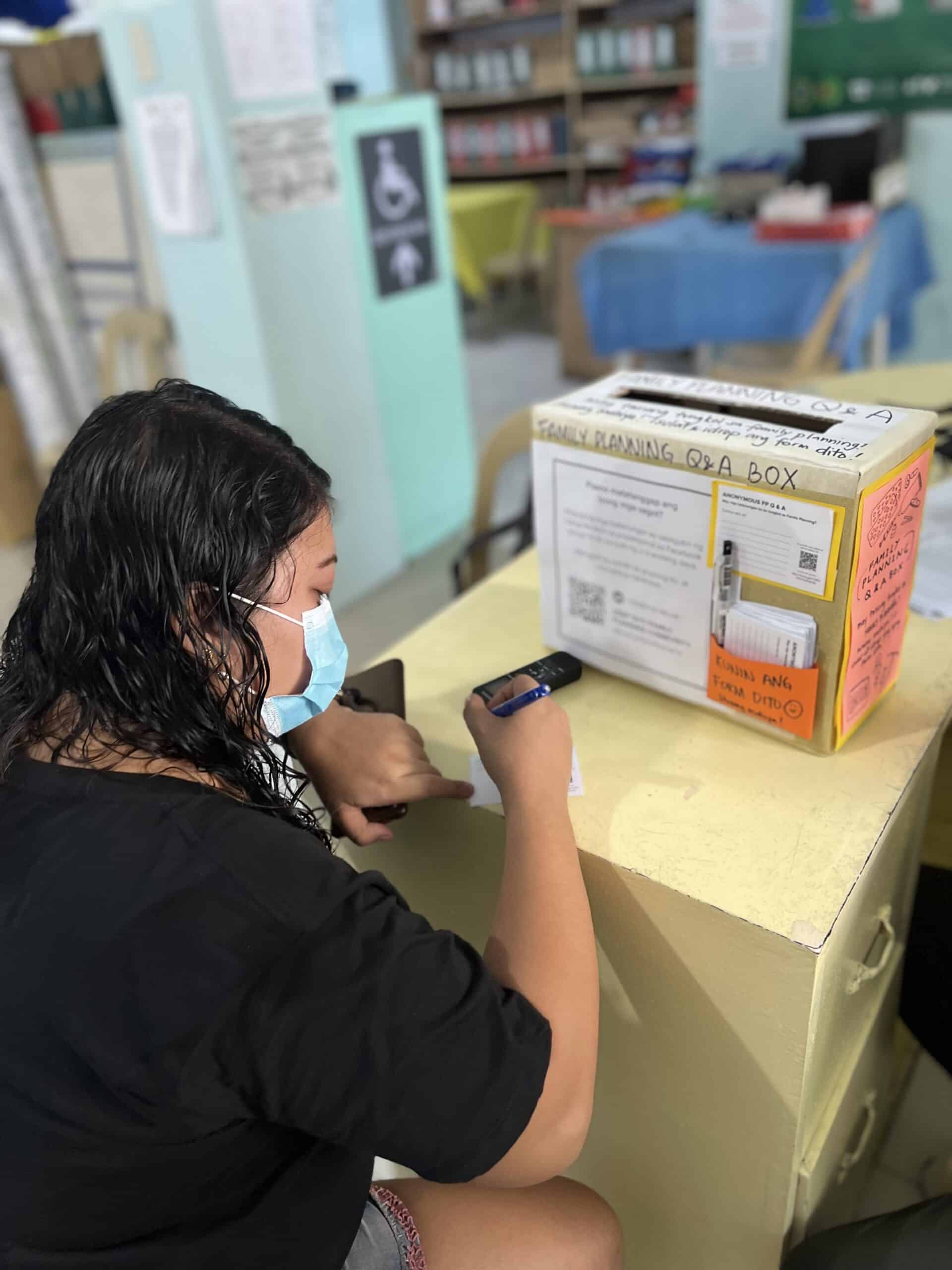

One prototype is the Anonymous Box and Bulletin Board, where women can anonymously leave sensitive or intimate questions about contraception while maintaining their privacy and protecting their identity – and then get the answers. Another is a couples’ family planning event where they can engage in candid conversations about family and contraception and learn about the benefits, challenges, and potential side effects. The prototype includes a facilitation guide, activity flash cards and a certificate.

The group also created digital #LetsTalkContraception stickers designed to prompt family planning conversations on Viber, WhatsApp, Messenger, or other social media platforms. The stickers depict an iconic character and encourage users to talk about contraception and side effects and to visit a health care provider. Providers send the sticker sets to clients, who then share them within their social circles, reaching women outside who haven’t been to the health clinic.

The team received positive feedback during the dissemination event held in Manila, Philippines in January 2023, and a global webinar in March 2023. “I look forward to seeing how these prototypes will evolve as they are localized in the Philippines and in other countries,” Murga says.